Narratives—feedback written by teachers and received by students at the end of the fall and spring semesters—summarize a student’s progress and performance over the course of the semester, from a teacher’s perspective.

According to Upper School Assistant Division Head Claire Yeo, written evaluations provide students with individualized recognition, rather than reducing achievement to a single letter grade.

“Reading narratives gives me a more full picture of how I’ve done in someone’s class [instead of] an A or A minus,” said Daniel R. ’25.

The writing in narratives consists of “a variety of performance factors, including skills and practices, content knowledge, and class participation,” said Yeo.

According to Yeo, teachers are expected to write roughly 200 words—though many teachers exceed that word count suggestion.

When writing, I-Lab teacher and 12th grade dean Morgan Synder asks herself, “What were their grades? How did we check in? What was the feedback I gave them at midterms? Did they respond to that? And that will take me longer because I’m just pulling from more material.”

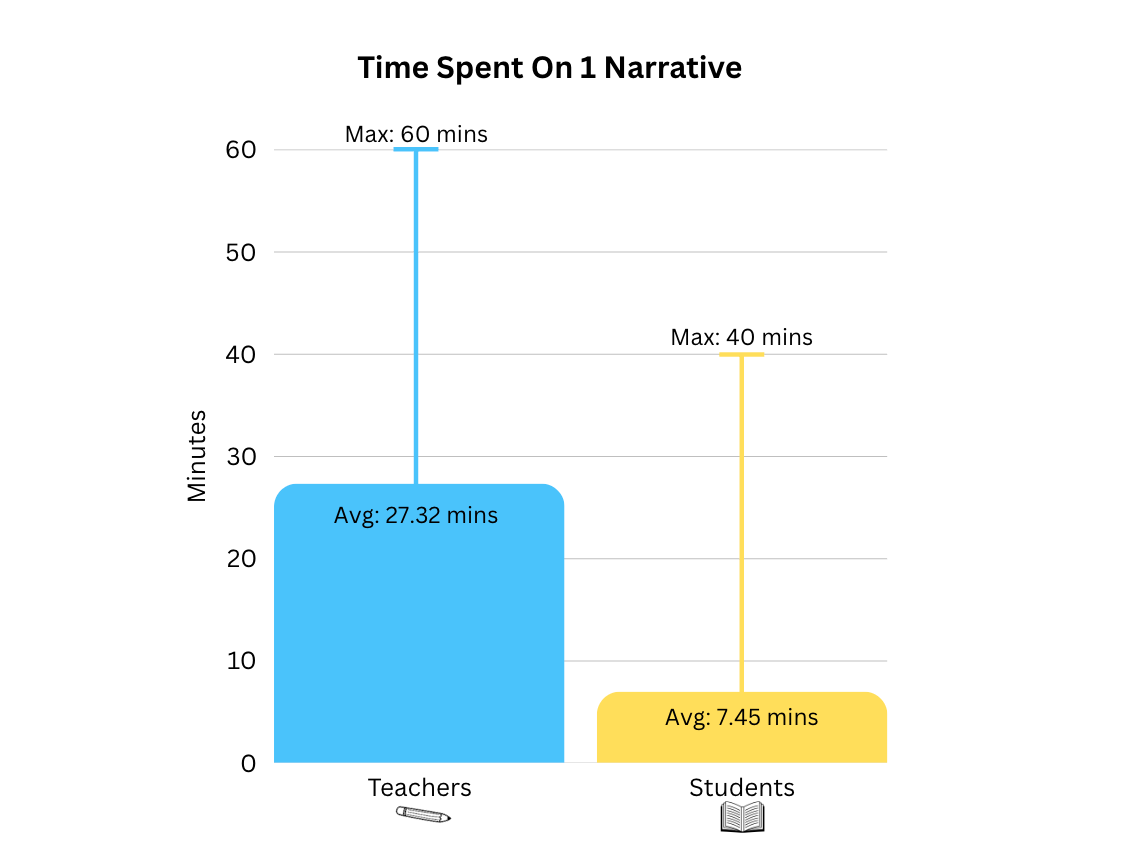

In a survey of 141 Upper School students, 78% of students spend zero to 10 minutes reading a single class’ narrative. In comparison, the average teacher spends 27 minutes on each student’s narrative. Over four separate classes, the total amount of time spent writing narratives can reach 35 hours.

“It’s time consuming and mentally challenging to write so much because we have a certain amount of time to do so many narratives,” said Upper School Spanish teacher Paloma Fernandez-Mira. Most teachers write narratives over the course of two to three weeks at the end of semesters, remarked Yeo.

Narratives are released a couple weeks after the end of the semester alongside rubrics and letter grades. While narratives are addressed to the student, they are intended to be read by parents as well.

“My parents are the type of people that really love written feedback so they really like it when they get a piece of paper that says, ‘Here’s how your son is doing well and here’s how they can improve,’” Daniel said.

In addition to narratives, students have parent-teacher conferences with all teachers. These 10-minute meetings, which occur at the midpoint of the semester, offer an opportunity for a conversation between student, teacher, and family members. However, only 18% of surveyed students said that conferences were the most helpful, compared to rubrics and narratives—which 50% and 32% of students, respectively, found the most helpful.

Contrary to survey results, Fernandez-Mira prefers conferences. “I can express enough in the narrative, but I would prefer more of a dynamic conversation,” she said.

In the past, narratives, parent-teacher conferences, and rubrics were offered at each midterm and semester end; now, only rubrics are sent out four times a year. The change occurred after COVID, due to teacher workload and stress, according to Yeo.

Before the switch, “faculty found themselves constantly writing narratives, producing rubrics, and determining grades… It swiftly became apparent that that was far too onerous to be productive. We want teachers to be creative and to be interacting [with students], not sequestered, writing narratives all the time.”

No matter the schedule, narratives, conferences, and rubrics all offer different aspects of a personalized evaluation. Yeo believes narratives still serve the same purpose: “to show the complexity and nuance of the personality,” and “[celebrate] the student.”

Additional reporting by Libby E. and Zadie K.