“Who does Trump and his administration see as a criminal right now?” Adriana Cortes* asked a room of San Mateo County residents last week.

Cortes, a community organizer through national faith-based nonprofit Faith in Action, paused as the room went silent. Slowly, attendees came to the same conclusion: “Todos nosotros.” All of us.

The members of Faith in Action’s San Mateo County chapter are mostly immigrants from Central and Latin America. According to the census, they are among the foreign-born residents that make up 35.6% of San Mateo County’s population. There are over 265,000 immigrants out of the region’s 745,000 residents.

In recent weeks, many immigrant families throughout the United States have grappled with anxiety, fear, and confusion, as they anticipate increasing challenges to remaining in the U.S. under the Trump administration. In response, organizations are quickly adapting and rallying to protect their rights in hopes of staying in America.

Many local businesses and street vendors participated on Feb. 3 in the “A Day Without Immigrants” protest to raise awareness about the positive economic and cultural contributions of immigrants to America. On Feb. 6, hundreds of high school students from schools such as Sequoia, Menlo-Atherton, Woodside, Summit Prep, Tide Academy walked out of their classes in protest of deportations.

They rallied around some of San Mateo County’s most vulnerable residents who face deportation: undocumented immigrants, who live in America without legal immigration status.

This may mean that an immigrant entered the country illegally, entered legally but overstayed, or is in the process of gaining citizenship. It is a civil offense but not a crime to be undocumented, and immigrants with U visas or green cards are not considered undocumented. At present, there are an estimated 11 million undocumented immigrants in the U.S.

In 2019, the Migration Policy Institute estimated that there were 55,000 people living without legal authorization in San Mateo County.

President Trump has long sought to deport and stop the arrival of undocumented immigrants. In the 2016 presidential race, he frequently discussed building a physical wall along the U.S.-Mexico border to prevent immigrants from crossing into the country. In his 2016–2020 administration, he deported about 1.2 million people. Notably, former Presidents Barack Obama and Joe Biden each deported more people per year than Trump did in his first term.

“The reality is that there is no difference when quantifying deportations. The deportation machine continues to work regardless of who is [president],” Cortes said. “The problem is the way they’re doing it. When it’s Democrats, they are doing it in the darkness. No fear or threats, just direct action. The problem with this administration is the way they’re treating people before they start to take action.”

For his second presidential campaign and administration, Trump has made immigration and securing the border even more of a central topic. In a speech in Iowa in late 2023, he stated his intention to “carry out the largest domestic deportation operation in American history.”

Now that President Trump is back in the Oval Office, he has already taken significant action surrounding immigration and border security. His stated aim is to protect the country from drug cartels and foreign terrorist groups. Research in 2024 from the American Immigrant Council showed that higher immigrant population shares do not increase crime rates in the U.S.

President Trump has signed seven Executive Orders related to immigration, including one named “Securing Our Borders,” which moves to create a physical barrier on the U.S.-Mexico border and cancels use of the “CBP One” app, an app that immigrants used to navigate immigrating to the U.S.

Another is named “Protecting The Meaning And Value Of American Citizenship,” which ends birthright citizenship and only recognizes citizenship for newborns if their parents are both citizens. Federal District Judges John C. Coughenour and Deborah L. Boardman have temporarily blocked the implementation of this specific policy. Judge Coughenour stated that President Trump’s proposed end to birthright citizenship is “blatantly unconstitutional.”

Trump also appointed former acting director of ICE, Tom Homan as the “border tsar” for the United States. At the Republican National Convention, Homan addressed undocumented immigrants. “You better start packing now,” he said.

Redwood City resident Maria Velasco*, who immigrated from Mexico in 2000, is deeply worried about the impact of Trump’s strong anti-immigration policies in San Mateo County.

“I feel that we are in a pandemic—an emotional pandemic. Whether they have papers or not, everyone is terrified thinking about what is going to happen. Is their family going to be separated?” she questioned.

Another one of Trump’s Executive Orders is “Protecting the American People Against Invasion,” which calls for a pause in federal funds to regions which maintain sanctuary status—an area where local cops are more limited in aiding federal immigration officers. California, leading the country with 1.8 million undocumented immigrants, is one of the nine states that may be affected by this new policy.

In 2023, San Mateo County adopted a sanctuary ordinance to prevent its local authorities from supporting federal agents. Other Bay Area counties like San Francisco County, Alameda County, Santa Clara County, Napa County, Contra Costa County, Sonoma County, and Santa Cruz County also have similar sanctuary ordinances.

Still, San Mateo County residents are extremely worried because of Trump’s nationwide expansion of immigration authority activity. In addition to the aforementioned orders and appointments, two weeks ago, Trump allowed ICE to enter more “sensitive areas” like schools and places of worship. ICE was previously unable to enter these locations.

“Criminals will no longer be able to hide in America’s schools and churches to avoid arrest,” said Acting Deputy Secretary of Homeland Security Benjamine Huffman, who was appointed by President Trump.

But deportations and arrests are targeting more than just criminals. Per NBC News, of the 1,179 people arrested on Jan. 26, 52% were labeled as “criminal arrests.” At least 566 people arrested had not committed any crimes.

Just south of San Mateo County, in San Jose, the Santa Clara County Rapid Response Network confirmed that ICE made at least one arrest in late January. San Jose officials confirmed that ICE has been active multiple times in their city, though local police have not been aiding the federal organization. Further north in San Francisco, ICE has been active in downtown office buildings, according to California State Senator Scott Weiner.

ICE agents do not announce when or where they will be appearing, making arrests, or conducting raids. They sometimes drive in civilian vehicles and wear civilian clothing, while other times they drive official ICE vehicles and wear uniforms.

This makes it difficult for local immigrants to predict how they might encounter the federal officials. As a result, immigrant-frequented locations around the community are emptying as people stay at home out of heightened caution.

Paloma Ojeda*, a Nueva junior who spoke on condition of anonymity for her family’s privacy, described the emptiness of her local neighborhood, where many Latine people and immigrants live. “It’s so quiet. Hardly any [stores] are open—or if they are open, it’s just very slow,” she said. “Everyone’s scared for their lives to step out and go to these businesses.”

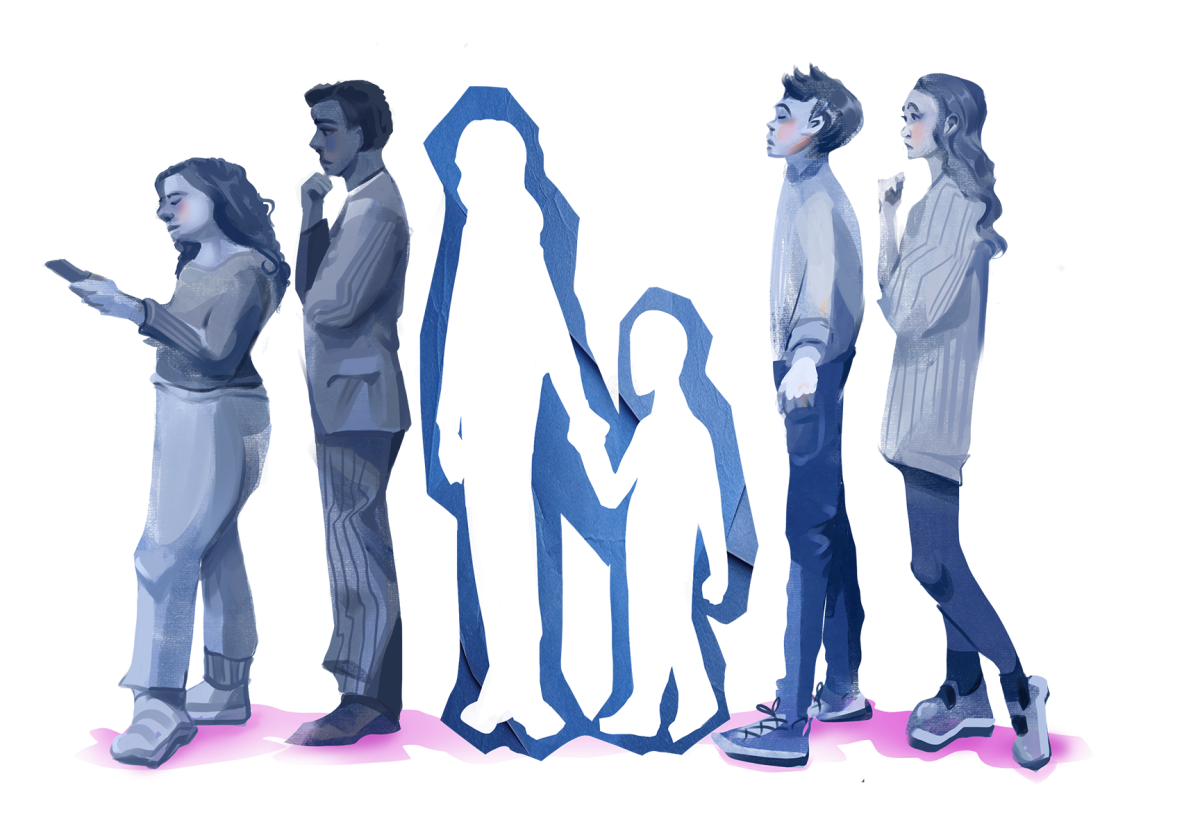

Ojeda, who is the only native-born member of her immediate family, was 8 when Trump first came into office. The president’s anti-immigrant sentiment made her worry about becoming separated from the rest of her family, who were not yet all U.S. citizens.

“That’s kind of when it all started. Being fearful of even going into the streets with my family, being scared that one of us would be picked up and maybe never seeing them again. And that fear has kind of just stuck until now,” she said.

Many others are living in fear of deportation breaking up their families, including Elvi, a service provider in San Mateo County. She is an undocumented immigrant from Mexico with a 15-year-old daughter and an 11-year-old son. Elvi crossed the border for $1,500—a significant financial sacrifice for her family—when she was 20.

“I can’t sleep because the fear is for our children. If they grab you, and you don’t have time to go get your children…” Elvi trailed off. “I love my children. I don’t want my children to grow up without their [parents].”

Elvi’s worries for her children are well founded. Beyond their immediate emotional impacts, President Trump’s moves toward mass deportation may also cause short and long-term health problems for young children, according to pediatrician Dr. Amy Kostishack P ’25.

Dr. Kostishack works at Santa Clara Valley Medical Center, where her patients’ families come from around the world. She sees a significant number of Latine patients, who are sometimes undocumented or have at least one undocumented parent. She worries that the removal of parents from their children could qualify as an Adverse Childhood Experience, or ACE.

ACEs, Dr. Kostishack said, have been scientifically proven to change the physical biology of a young person. “If you were to separate a child from their parent, or if you were to take a child and put them into a country they’re not familiar with, it’s only expected that they are likely to experience extreme stress and trauma,” she said. “These stresses can trigger physiologic changes that can affect their development and wellbeing in childhood and can lead to chronic disease in adulthood.”

The undocumented parents of these children often have very few options for pursuing secure citizenship in America.

US Spanish teacher Francisco Becerra often hears other people wonder why undocumented immigrants do not attempt to get legal authorization. Becerra himself applied for a U.S. green card with his family while living in Mexico as a middle schooler. It was only 8 years later—after Becerra had graduated university in Mexico—that his family was finally granted authorization to live in America. They had two months to immigrate and eventually settled in North Carolina. Five years later, Becerra applied for and was granted U.S. citizenship.

The total process of gaining U.S. citizenship took Becerra 13 years. From his personal experience, legal immigration is often “complex or impossible if you don’t have a connection,” Becerra said.

Like Becerra, Ojeda’s father had a similar experience of waiting years for citizenship. He came on a visitor visa from South America to California more than 20 years ago, seeking a better life with more opportunities, and he was only able to secure citizenship last year. Up until then, he had only held a green card because his daughter, Ojeda, was born a U.S. citizen. The long process of waiting “[puts] it into perspective how broken the system is,” Ojeda said.

For Elvi and her family, applying for citizenship is daunting and difficult. Because of the 1996 Illegal Immigrant Reform and Responsibility Act, immigrants who have resided in the U.S. illegally between 180 days and one year may apply for citizenship—after exiting the country for three years. Immigrants who have stayed for more than a year are allowed to apply for citizenship after a 10 year ban from the U.S.

Elvi has lived in California for nearly 17 years.

“I understand that we are in a country that is not ours, and we have to respect the laws,” she said. But she broke down crying at the thought of being forced to leave the country where she and her husband have built a life for their two children.

Elvi and her husband grew up in Oaxaca, a Mexican state with different smaller Indigenous groups. Her first language was Zapotec, which has 500,000 speakers. She learned Spanish when she was 12 and was an avid learner from a young age. Given her family’s limited income and financial opportunities, Elvi was unable to fulfill her dream of pursuing higher education after graduating high school in Mexico. It was only in America, after obtaining a high school diploma in English, that she began to dream of one day attending university.

Elvi hopes to obtain citizenship one day so that she can attend school, learn more English, earn a college degree, and apply to a white-collar job. “I always tell my husband, ‘I would like to work in an office and dress nice,’” she said.

Other immigrants in San Mateo County find it impossible to return to their home countries. Cortes said that she never thought that she would immigrate to the U.S., but experiencing violence and poverty in Mexico forced her family to flee from their home.

“Returning has not really been an option because our lives were in danger,” Cortes said. “For many families I know, if they return to their country, what awaits them is no kind of life.”

She added, “I have met people over the years who have been forced to return and have found death.”

With limited options to secure legal status or return to their native countries, undocumented immigrants have been bracing for encounters with ICE and preparing their families for the worst-case scenario—deportation and separation.

assembles stacks of red cards for distribution at churches and community events. (Kayla L. ’27)

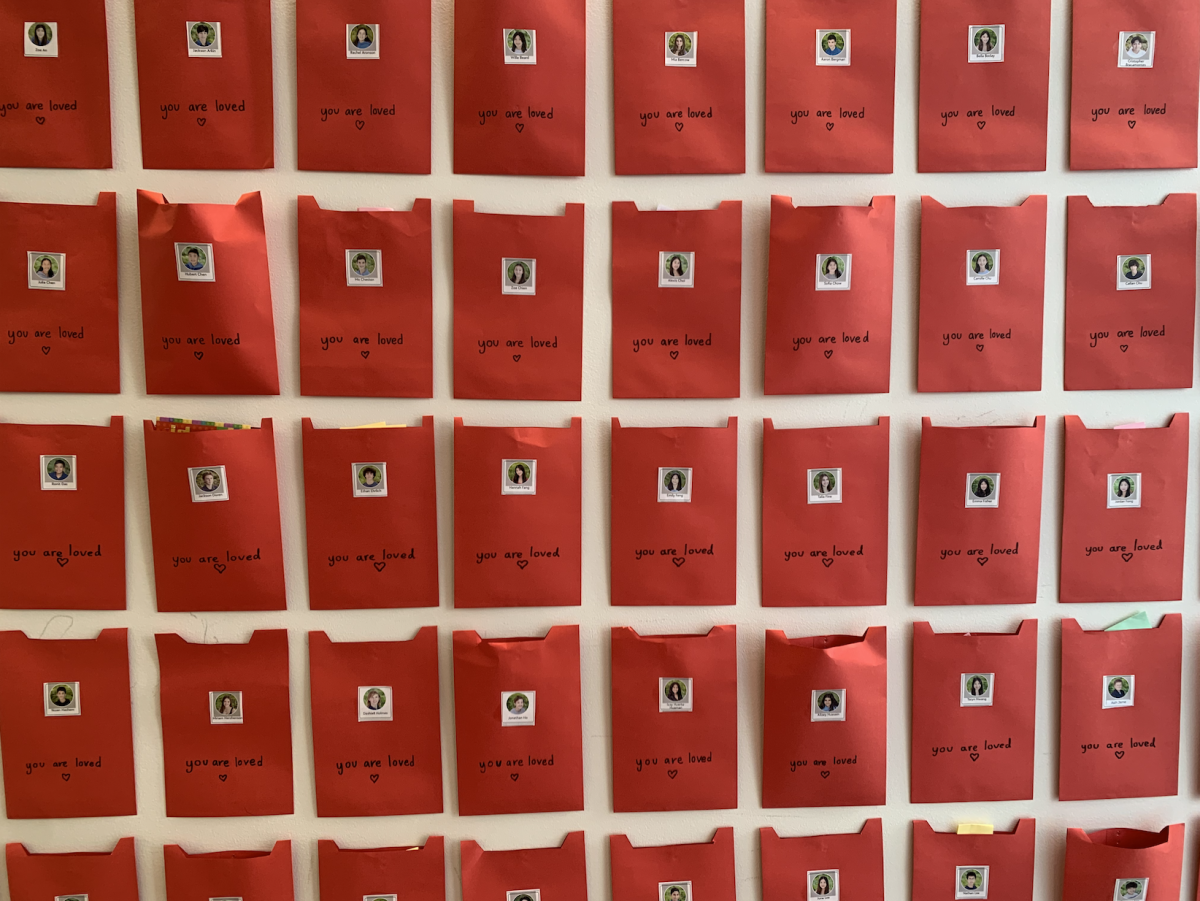

At Faith in Action’s Bay Area office, chapter members have been signing up to spread information about ICE preparation and to distribute tarjetas rojas, or red cards, around churches in San Mateo County. The size of a credit card, red cards were created by the Immigrant Legal Resource Center (ILRC) in 2007. The cards contain reminders in English, Spanish, and 17 other languages about constitutional rights, which apply to anyone on U.S. soil regardless of citizenship status.

“I do not give you permission to enter my home based on my 4th Amendment rights under the United States Constitution,” reads one line of the card. According to ILRC, there have been 9 million requests for cards since the election of President Trump.

Elvi, Cortes, and Velasco have been carrying Spanish versions of the cards in their wallets, while Dr. Kostishack’s office has been distributing them to patients who come in for office visits.

Cortes described seeing this collective action in recent weeks as “beautiful.” Beyond tabling around the community and passing out red cards, Cortes is also one of the founders and chief leaders of the San Mateo County Rapid Response Network, which is a hotline that San Mateo County residents can call into and request for verification of immigration authority activity in the community.

Verifying these calls is important because panic can spread quickly among immigrants when it comes to sightings of ICE or other authorities. Undocumented immigrants should remain calm until rumors have been confirmed by officials or hotline operators, Cortes said.

Attendees of the recent Faith in Action meeting spent a few minutes memorizing the digits of the Rapid Response Hotline, so that they can call for help even in a moment of fear or worry: “Dos. Cero. Tres. Seis, seis, seis. Cuatro, cuatro. Siete. Dos.”

Regardless of their immigration status, each member noted down the number (one mother brought three of her children to this 7 p.m. meeting). Their common trait had nothing to do with their citizenship status—it was their shared Mexican ethnicity.

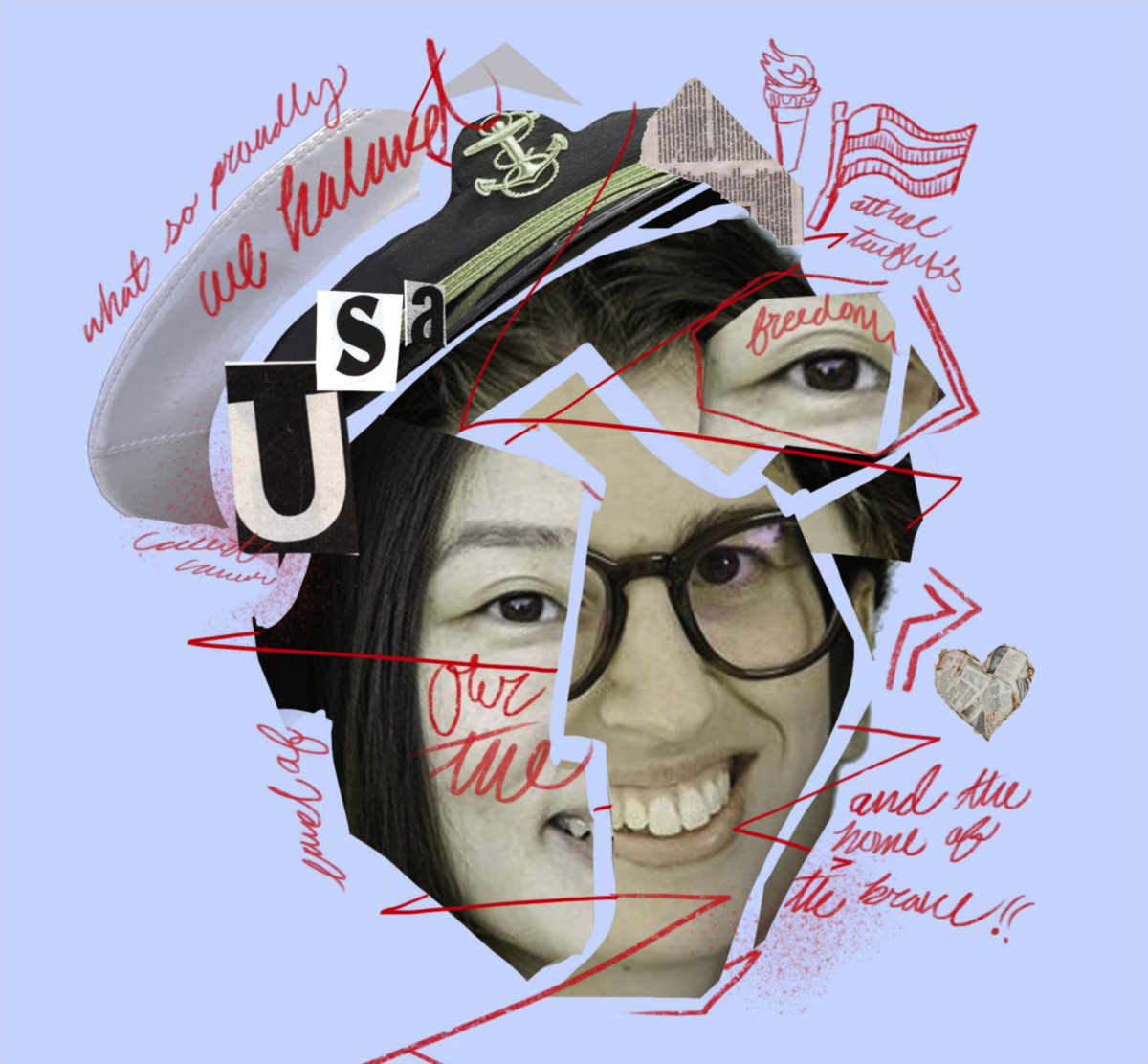

This is because President Trump has frequently taken the actions of a few select undocumented immigrants and falsely extrapolated them to the broader community of immigrants in America.

Of America’s 11 million undocumented immigrants, 4.8 million are from Mexico, and at least 2.8 million more are from other countries in Central and Latin America. Unfortunately, these immigrants and the general Latine American population have been subjected to harmful generalizations by President Trump, his circle of staff, and the media.

Becerra called out a common misconception. “There is a concept that a Latine is the same as a migrant. It is completely—” Becerra paused. “Many [Latines] in California have lived here longer than other people,” he said.

In 2015, during his presidential campaign announcement, President Trump said that he believed immigrants from Mexico are “rapists” and that “they’re bringing crime.” In 2023, he said that immigrants are “poisoning the blood of our country.” More recently, President Trump has alluded to immigrants as “snakes,” “violent,” and “insane.” In many of the president’s Executive Orders, he refers to undocumented immigrants as “illegal aliens,” a deliberately dehumanizing term.

President Trump labels undocumented immigrants as criminals—and there are, indeed, undocumented immigrants who are criminals. In 2024, under former President Joe Biden, the U.S. Border Patrol arrested 17,048 undocumented immigrants with criminal convictions of assault, illegal drug possession, and more—this accounts for 0.15% of all 11 million undocumented immigrants. Nonetheless, President Trump has magnified that small segment of the demographic in his policy agenda.

The Laken Riley Act, a piece of legislation President Trump signed into law on Jan. 29, instructs the deportation of undocumented immigrants that have committed violent crimes like assault of a police officer and non-violent crimes such as shoplifting. The act is named after Laken Riley, a 22-year-old Georgia nursing student who was murdered in 2024 by Jose Ibarra, an undocumented immigrant from Venezuela.

Elvi acknowledges that dangerous people like Ibarra exist within the immigrant population. She hopes that authorities know that her family and “not all of [immigrants] are criminals.”

Because of how Trump, the media, and other political leaders have publicly connected having an immigrant identity with having a criminal identity, the Nueva student often wonders about others’ perception of her or her family, and “if people are taking these words and applying them specifically to Latines in their lives.”

“It’s a fear of what people are thinking about me, or if they think that I or my family might somehow be threatening to them,” she said.

Other ethnic immigrant groups are struggling with similarly disproportionate or false claims by President Trump. During his first presidential debate against former President Biden, Trump incorrectly claimed that Haitian immigrants in Ohio were “eating the dogs” and “eating the cats.”

In April last year, President Trump commented on the influx of “military-age” Chinese immigrants into the country. “It sounds like to me, are they trying to build a little army in our country? Is that what they’re trying to do?” he questioned a rally crowd in Pennsylvania.

There are an estimated 390,000 undocumented Chinese immigrants in America, and 110,000 reside in California. Indians and Filipinos immigrants are also undocumented in high numbers, with 120,000 and 152,000 undocumented immigrants living in California, respectively.

According to Jenny K. Hong, the Managing Attorney at Omega Immigration Law, “There are many undocumented Asians living in California, especially in the southern part of California, as well as the Bay Area.”

“Many of the undocumented immigrants living in California do not have a path to citizenship,” Hong said. “Most people falsely believe that living in the U.S. for so many years or marrying a U.S. citizen can grant paperwork, but that is just not the case.”

“It’s important that people understand families in our community that now need to make very difficult, very sad decisions,” Becerra said. He hopes that Nueva might coordinate intentional conversations about immigration and invite in a guest speaker with expertise about the nuances of immigration in the U.S.

Listening to President Trump and seeking alternate viewpoints will “support the communities that are being affected, and [you can] personally understand the problem more,” Becerra said. He believes that gaining a diversity of perspectives is critical for understanding the complex immigration system in America. “If we only have one version, many people end up believing that it is the absolute truth.”

*Name changed to protect the anonymity of this individual.