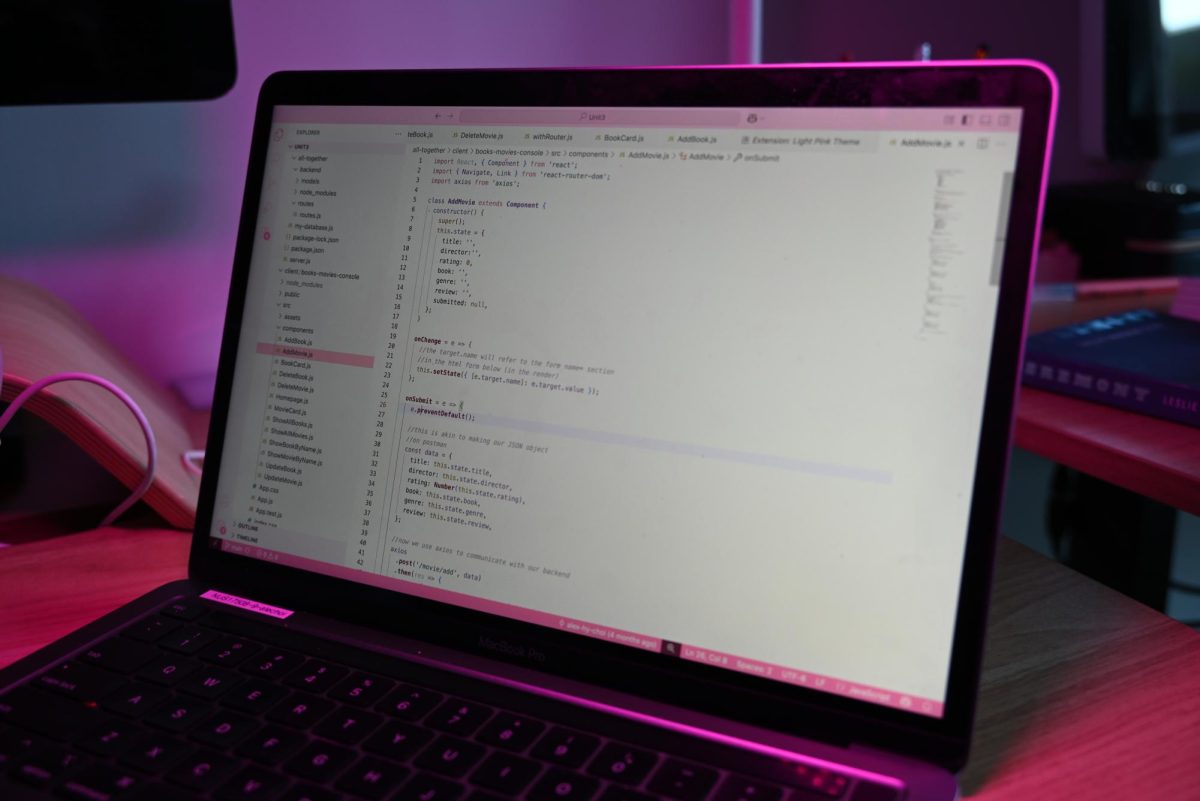

“Why don’t you make friends with some coders?” my parents would ask seventh grade me—to which I’d reply, “They’re all boys.”

This was the conversation—not an unusual one—I had after coding club in middle school. During those lunches, I worked at a table alone. While I made small talk with my teacher and wrote simple animations in Javascript, the boys across the room seemed to be much more advanced than I was. I never talked to them once.

I wasn’t shy. But, as the only girl in the room, I felt insecure about my ability to code and the projects that I had made. Was my work too superficial, too silly, too ‘girly’?

Regardless of whether I was actually judged—and as I look back, I don’t believe I was—social stigma surrounding women in STEM made me feel hesitant about coding.

Never have I ever heard a girl my age declare, “I love computer science.” When CS was a required course at the middle school, all I remember hearing were complaints from the girls, and excitement from the boys. Small droplets of stigma found their way into the mind of the middle school girl, and stuck.

I have taken three computer science courses at the Upper School and; needless to say, I’ve enjoyed each class. However, as I look back, why was I nervous about being only one of two girls in my six person class? Why did I feel as if my projects needed to be the best in the room for me to present?

In CS terminology, debugging means to fix errors. After ninth grade, I hoped that the solution to my “bug” would be an all-girls Artificial Intelligence and Machine Learning summer program. However, once I arrived I found myself frustrated, stuck, and confused. I wasn’t hesitant about the coding, but how it was presented: as a friendly, low commitment hobby.

I felt as if I was being told, “You should learn computer science—for fun.” Was this how programming was being taught—for girls?

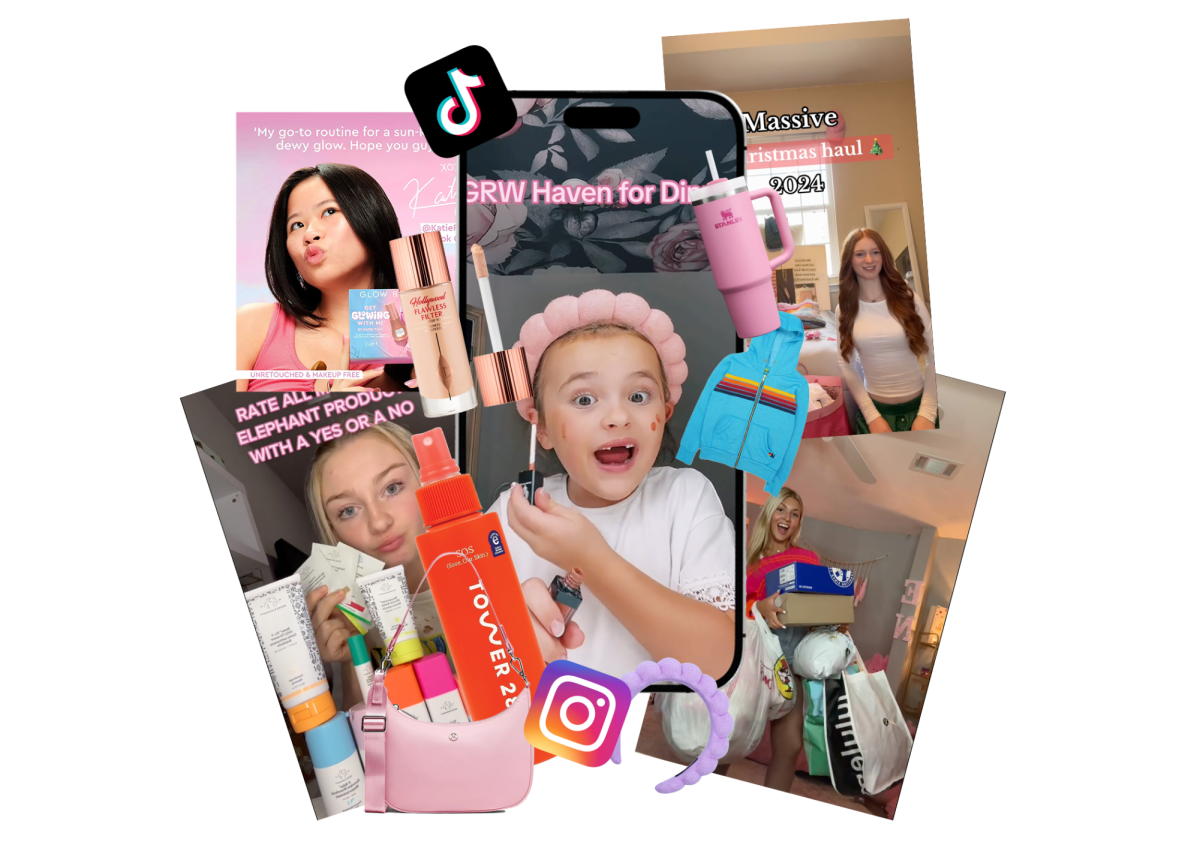

On Wednesday we wore pink, and we filmed group TikToks as a “brain break.” I felt babied; this was our “soft launch” into CS, and we spent only two hours out of the seven a day coding.

I wasn’t expecting to do revolutionary work in one week. Wrapping STEM up in a tidy package with a glittery, however, was not counterproductive. I walked away from that week more excited for the snacks.

That being said, the fully female environment did facilitate positive social interaction. I bonded with girls and talked a lot with my teachers and TAs.

Still, I don’t believe that all-girls environments are the most effective for deepening the engagement of women in STEM fields.

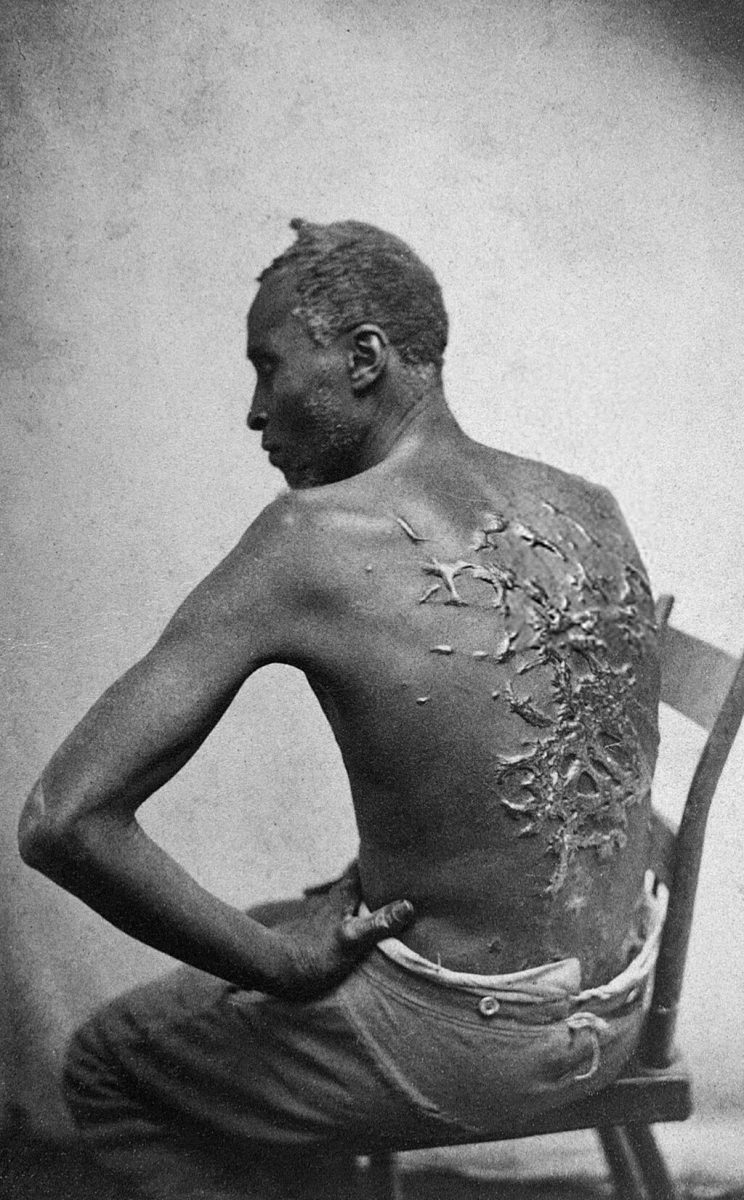

It’s a fact that women are still underrepresented in STEM fields; as of 2023, only 26% of workers in STEM were female, according to the U.S. Department of Labor.

There is sufficient evidence to prove that societal issues are at the root of gender disparity in STEM, especially in earlier years of education. In a University of Illinois study, 62% of boys in grades K-3 named STEM subjects as their favorites, while only 37% of girls did the same.

Equity is not equality, and marginalized groups need more assistance than others. Girls in STEM do need more encouragement, but I’d like to add another consideration: isolating girls in STEM might further single them out. In a program with a curriculum designed for teenage girls, I was expected to act and have the same interests as a stereotypical one.

Taking boys out of the equation is not the solution—that’s just not possible in “real life”—but there are other ways we should seek to improve girls’ experiences in STEM fields. We should encourage girls to code, and then help them feel comfortable and confident in all-gender environments.