Anwen C. ’26

PART I: AI IN THE HANDS OF STUDENTS

The story was short. Not even half a page long, the tale involved aliens and starry space, composed by Hannah F. ’27 and a friend while in the throes of boredom. There was also a third contributing author: ChatGPT.

Hannah was in 8th grade and experimenting with prompting a generative artificial intelligence (AI) chatbot for the first time. A story, based on an idea she and a friend had already come up with, seemed like a good idea. Within a few seconds, the screen filled with words. Hannah was shocked by the speed of the whole process, and the personable, adept tone the chatbot used to communicate.

In the three years since OpenAI launched GPT-3.5 to the public, that initial surprise has faded completely. Now, Hannah would be more surprised if any student in the Bay Area—a tech hub where billboards for AI line the highway and OpenAI holds three offices—has been able to completely evade AI.

“I don’t think you can avoid it—or at least, it’s pretty difficult,” Hannah said.

In particular, she pointed to ever-present tools like the Google AI overviews, AI-generated summaries that automatically appear at the top of search results.

“[The overview] comes up and you automatically read it. It’s forced convenience, in a way,” Hannah said.

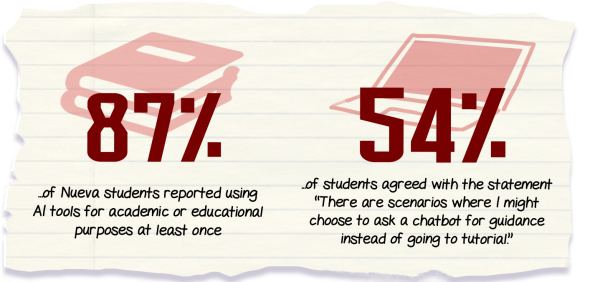

The prevalence of AI is a well-recognized part of the Nueva student experience. According to a recent survey with a sample size of 100 students—about a quarter of the Upper School student body—87% of Nueva students reported using AI tools for academic or task-related purposes at least once. Chatbots like ChatGPT and Google’s Gemini, as well as Google AI overviews , ranked among the most common AI tools students engage with.

The rise in AI usage and reliance has been consistent amongst all levels of education. It has not gone unnoticed by AI developers. In recent months, major AI companies have moved to capture a wider student audience, promising tools that will accelerate and enhance the learning process. New products like OpenAI’s “study mode” and Gemini’s “guided learning” are advertised as interactive tutors and often paired with free trials to premium models to draw students in.

As AI tools have become more widespread, academic institutions have attempted to keep pace, with mixed results. At the university level, colleges such as Duke University and California State University have begun to implement AI use on their campuses, spending millions of dollars to offer unlimited ChatGPT accounts to their students. At colleges such as Ohio University and the University of Michigan, AI fellow programs have been established to support faculty integration and exploration of AI in teaching and scholarship.

Yet alongside these efforts to encourage AI use, tensions have occasionally surfaced around the use of AI by both students and faculty. In one recent case, a Northeastern University senior filed a formal complaint with the business school, alleging that a professor’s use of AI-generated lecture notes was hypocritical in light of the university’s strict policies on student use of AI tools.

With no standardized framework governing AI use in education, schools across the country have had to construct their own policies. At Nueva, this has taken shape through several rounds of policy revisions, with much of the practical details falling to individual teachers to interpret and implement.

As a member of the Bay Area AI Cohort, a coalition of private schools discussing how best to regulate AI, the school has hosted dialogue about AI use on faculty development days and hosted a panel where students discussed their AI use. Another such faculty development day on Oct. 19 will continue the ongoing conversation.

In addition to examining AI case studies, philosophies, and policies, the administration intends to share a new AI policy grounded in Nueva’s school values. The policy will clarify certain restricted uses of AI tools, while still maintaining each teachers’ individual agency and freedom to direct AI use in their classroom.

Up until this October, Nueva has been in an “exploratory transition period” with regards to the school’s AI policy, according to Dean of Academics Claire Yeo In practice, this ambiguity has meant that the acceptability of AI usage has been decided on a case-by-case basis. Teachers have defined what is allowed in their classroom, as student usage patterns have evolved.

The clearest AI-related boundary for students is the restriction of AI-generated writing—notably in English and History classes, where written work remains the core method of assessment. Violation of this guideline leads to notification of advisors and parents, and possible disciplinary action.

However, the essay pre-writing stage is still occasionally a gray area: students and teachers continue to grapple with whether AI can be used in idea generation and brainstorming, revising, and outlining.

Penelope C. ’26 categorizes acceptable AI use in English classes as situations where the AI tool is treated like a peer. For example, it is acceptable to bounce ideas off of the chatbot, have it check grammar, or suggest stronger adjectives and verbs.

Still, despite these relatively limited uses of AI, Penelope is hesitant to completely endorse AI in the writing process.

“There’s a very fine line between using AI as a crutch versus using it as a tool,” Penelope said.

That distinction remains ambiguous at times for Penelope, even though she would characterize herself as supportive of AI use in education. At home, she has grown comfortable with generating extra practice problems or flashcard sets for math and prompting ChatGPT to help explain concepts when she is confused. Still, Penelope acknowledged the potential for academic dishonesty and the ensuing possible deterioration of students’ skills.

“I worry how usage is affecting students’ capabilities to think critically on their own,” Penelope said

Concerns over detrimental long-term effects of ChatGPT have begun to emerge amongst other students of all ages. Elyse D. ’29, who has witnessed AI’s growing prominence since the beginning of middle school, expressed worry over what student usage of AI means for adaptability and intelligence. Her usage is relatively rare, though she likes to occasionally experiment with queries and practice problems.

“It’s scary to me, because if we have AI to do all this stuff for us, then we’re not actually gonna learn how to do it ourselves,” Elyse said.

Hannah has begun to witness these regressive consequences in herself, specifically around email writing. She often uses ChatGPT to refine her emails before sending them, and while her ability to write emails has not necessarily diminished, Hannah still worries about becoming reliant on the technology.

“I have realized that as I use AI more, I am getting lazier when it comes to writing,” Hannah said.

Hannah intends to cut down on using AI for these brief tasks this year. However, she will continue to use AI for academic purposes like generating extra problems or physics explanations.

In the recent school-wide survey, similar usage patterns emerged. Several students described using AI to create practice problem sets, study guides, and flashcards in both STEM and humanities classes. Other times, students use AI to improve coding projects or make data analysis assignments easier. Most commonly, though, AI is used as a more complex and advanced search engine than Google. 72% of student respondents reported using AI to search for information or ask a question.

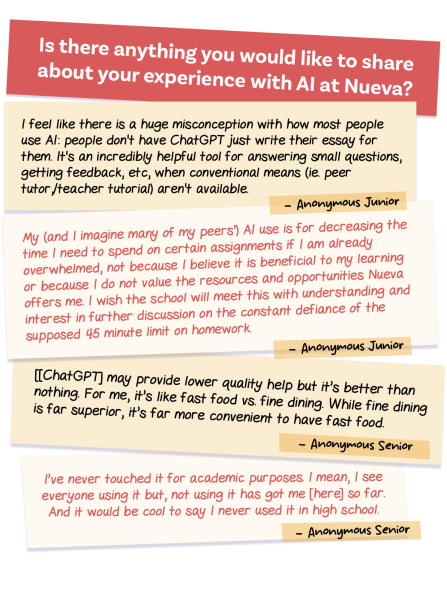

In some cases, this use of ChatGPT will even replace meeting with a teacher for a tutorial. Survey respondents were somewhat split, with 54.3% of respondents declaring that there are scenarios where they would choose to ask a chatbot for guidance instead of scheduling a tutorial with a teacher. These respondents alluded to time concerns, as well as unique opportunities for personalization. Yet among the 45.7% of respondents who would always prioritize a tutorial, some emphasized the value of human interaction and community, aspects they felt a chatbot could not replicate.

When Henry H. ’28 has a question, his decision of whether he will turn to a tutorial or AI is affected by the amount of help he needs.

“At times, it’s a lot easier to ask a chatbot rather than waste a teacher’s time on something that might be menial. Or, oftentimes you might have to wait days and days in advance to book a tutorial,” Henry said. “It’s also a lot more accessible just to be able to go to ChatGPT, ask your question, and get an instant answer.”

For Beckett B. ’26, that accessibility will affect whether he will use AI or sign up for a tutorial—but only for non-humanities classes. Especially for writing-specific feedback or idea generation, he will always turn to his teachers. In addition, he pointed to the general benefits of tutorials outside of just academic questions.

“In my mind, the main value of tutorials is to connect with your teacher[s]” Beard said.

Still, Beckett isn’t quick to rule out the value of AI. As someone who uses AI semi-frequently for more conversation or queries, Beckett thinks of the tool as simply another technological advancement, not unique in its ability to bring about good and cause harm simultaneously.

“I think it’s a little naive to say that there are no possible benefits to AI in education,” Beckett said.

Beckett cited a chess study he read about recently, where participants of a chess club were given access to an AI tool that could predict the best next move in chess for its players. Though new-to-chess and casual players quickly found their skills deteriorating as they fell into depending entirely on the AI to play chess, players who were quite devoted to playing and learning chess actually improved significantly with the use of AI, and retained their skills even when the tools were taken away from them.

“I think it’s the same with education,” Beckett said. “Someone who is inherently motivated to learn will work better in the AI environment, compared to someone who just wants to get the work done—and maybe that’ll create a divide.”

To Beckett, AI is best understood as a tool that can be engaged with in both healthy and unhealthy ways, depending on its user. No ban is necessary—instead, teacher-crafted AI policies provide an opportunity to steer students towards healthy and productive AI use.

However, some students acknowledged that placing full responsibility on teachers and faculty to police AI usage is not sustainable. Penelope noted how current AI detectors are not always accurate. As model capabilities improve, distinguishing AI-generated from human-written work may become a more difficult—if not impossible—task.

“It’s really hard to tell when people are using it, and so it’s hard to enforce AI rules,” Penelope said. “Ultimately it’s just best for the student to self-regulate and make their own decision to take control of their learning.”

What’s the last thing you asked AI?

PART II: LOOKING FORWARD

Two years ago, CS teacher Wes Chao spent an eventful spring semester investigating and thinking about the role of AI at Nueva. He pitched the idea to the administration as a way to understand the and started going to conferences on AI, talked with AI experts, and worked with a group of seniors survey students about their understanding of generative AI.

In addition, Chao spent time experimenting with the bot to assess its capabilities. He asked ChatGPT to analyze data, write an essay, and make a lesson plan for him.

The results varied. AI data analysis of energy usage saved him three or four hours of work on the second attempt, after he told ChatGPT that the first prompt had made a mistake. He brought the essay to a faculty and staff meeting, where humanities teachers graded it as worthy of a C+ only. The lesson plan was usable, though Chao found it generally unnecessary.

“I thought [ChatGPT] would be really good if I had to teach something I didn’t know anything about. It could curate the topic for me. But, obviously, it wouldn’t make any sense for me to teach a topic I knew nothing about,” Chao said. “In general, I think we’re at a point in education where you can teach yourself a lot of things by going on the internet, with Google searching, or looking at YouTube or AI. So the question is, where do I add value as a teacher?”

For Chao, an important part of teaching lies in the extra purpose he can imbue into his lessons beyond the bare basics, like a fun fact, an extra important principle for the future, or an anecdote from his career.

“AI can give you a list of topics about how to learn data science or computer vision, or whatever else I teach. But I think making topics interesting is harder. AI only knows generally what’s interesting to humans [and] can’t infuse these topics with relevancy,” Chao said.

Chao’s AI guidelines are informed by these principles. He allows and encourages his students to use AI to enhance their learning. However, he still writes every part of his lessons on his own, and urges his students to reflect on how AI will specifically help them in their work, case by case.

As a history teacher, Sushu Xia has a slightly more rigid and direct approach to guiding her students’ AI use. At the beginning of each semester, she goes over common AI pitfalls—unreliable information and a specific writing style, for instance—and provides non-AI alternatives to every possible scenario.

However, when a student approaches her with questions about AI usage in history work, she always hears them out. She also has outlined very clearly the uses of AI in history work she finds acceptable, such as a preliminary search for a word or event within a text that Google might not be able to handle, or help with citation formatting.

“I think that there is a niche for AI, and I think that the more we understand what AI can and can’t do, the easier it is to find that niche,” Xia said. “Overall, what I try to say is: if it’s a place that is a low stakes, high speed situation where there is human oversight, I can definitely see where AI can be used.”

English teacher Sarah Muszynski maintains a similar flexibility in thinking about students’ AI usage, based around the skills she hopes to instill within her students.

“Part of my job is to help students be critical thinkers, which includes critically evaluating the tools that are out there in the world. Just saying “no” [to AI] would be an externally imposed restriction that wouldn’t make them grapple with them at all,” Muzynski said.

Though Muzynski has seen some of her students misuse AI, she remains committed to understanding why students might do so, instead of immediately blaming students.

“[Misuse] is usually because they are feeling overwhelmed and pressed for time,” Muzynski said.

Chemistry teacher Jeremy Jacquot, having noticed similar reasons for use, believes that it is important for teachers to acknowledge the systemic issues within the current educational landscape that contribute to widespread student adoption of AI.

“We have to understand that this is a system we carry. If there’s a strong incentive for students to receive straight As, get into top tier schools, and end up with highly paid jobs, why would you not use the tools available for you to check off those boxes? There’s a fundamental disconnect going on there, and I totally understand why students would use [AI tools,]” Jacquot said.

For history teacher Alex Brocchini, who is one of the school representatives for Bay Area AI Cohort, the basic questions underlying this knowledge of students’ rampant AI use are key to guiding his own policies.

“How do I help students get into a position where they’re not scrambling at the last minute and where they feel like they’re invested in the product they’re creating? I think part of the reason why people turn to AI is because they believe that the thing that they’re doing is not worth their time,” Brocchini said.

As teachers better understand why and how students use AI in academics, some have begun to contemplate how they may reshape their own methods of assessment. Last spring, during a faculty development day, teachers participated in a full day of planned workshops around AI and critical discussions over reimagining education with the advent of AI. Brocchini, one of the organizers of the programming, described the moment as particularly interesting and eye-opening.

“AI provides an opportunity for us to rethink our assessment practices—for instance, what is a valid way to show skills that we are teaching that isn’t just writing?” Brocchini said.

In the near future, however, teachers are focusing on how they can best meet their students where they are currently with AI usage. For English teacher Jen Neubauer, honesty is the most important principle. Often, she has observed a general hesitation to have open dialogue from her students about AI, who might be nervous about how their teacher’s perception of them might change.

“If you’re using a tool, being up front and honest about it, and citing it is really important. I certainly want to be honest about anything that I generate or create,” Neubauer said.

Alongside acknowledgement of AI use, Jaquot has a simple philosophy around AI that he hopes his students may internalize.

“Do your due diligence. That’s the virtue I want to teach my students,” Jaquot said.

Yet as educators continue to weigh how to teach students responsible AI use, others have begun taking action by rethinking the design of these technologies themselves.

Nueva parent Alisa Menell is the CEO of Curioso, a children’s learning platform with a digital library featuring over 25,000 books, quizzes, and activities. This year, the team launched Ask Curioso, an AI resource built to channel curiosity rather than replace learning.

Unlike general-purpose chatbots, Ask Curioso offers users short answers with prominent citations that link directly to books in the platform’s library. The chatbot also adjusts recommendations to a child’s reading level, includes safety guardrails, and highlights follow-up resources to encourage deeper exploration.

Importantly, Menell emphasized the value of teaching kids media literacy—something reflected in the chatbot’s design decisions. Rather than obscuring citations or relegating them to small footnotes, the team deliberately chose to enlarge their citations so users are encouraged to seek out additional information.

“We think it’s really important that we not only allow, but encourage kids to fact check,” Menell said. “Read [the books] for yourself. Read the context around it. Don’t just take this snippet of an answer. We think that’s where the magic of learning takes place, and we want kids to go deeper.”

While the team continues to refine their chatbot in line with their educational principles, Menell ultimately believes that AI, if done right, can serve as a powerful resource for learning.

“I don’t think it should take the place of a teacher,” Menell said. “I don’t think it should take the place of a parent, a tutor, or even a book. I think it should help kids feel connected to learning—learning more and learning more deeply over time.”

That distinction of AI as supplement, rather than substitute, was echoed by Nueva teachers reflecting on the unique role of human educators.

“I’m certainly not of the mindset that AI is going to usurp teachers,” said Jacquot. “Teaching has so much to do with fostering a sense of belonging, helping students feel self efficacy, and helping them become independent learners. And that is just not something I see AI doing.”

Muszynski also emphasized that the core of teaching extends beyond delivering information.

“We’re experts in our content, but we’re also experts in Nueva students and how they learn,” she said. “AI might be able to know you on paper, but it’s not going to know you in the same holistic way.”

As AI—and its applications—continue to evolve, teachers and faculty alike hope to preserve that value of teachers at Nueva. Yeo described the policy, created in tandem with student and teacher input, as a first step forward.

“It’s time for us to articulate a vision, translate that to policy, and provide action items that are clear for students and faculty so they can spend less time speculating and more time doing what they do best—creating and thinking,” Yeo said.