The Student Handbook, throughout all eleven years of the Nueva high school’s history, has contained not a single word about when and how phones should be used. But changes are coming: an official phone policy will be introduced this fall.

“There is an active conversation, right now, going on with the administration and our deans, talking about an upgraded phone policy specifically, but also a tech policy in general,” said Jackee Bruno, Upper School Dean of Students.

The policy will include “clear instruction on not having phones out, including during the social hours like lunch.”

“We’re not actually looking to take away or store [phones],” Bruno said. “[But if] it’s out in a way that doesn’t fit the moment, let alone the policy, it’ll be taken away, eventually given back.”

Regulation of students’ phones is not just happening at Nueva—2025 has been the year of phone bans, with schools across the United States working to restrict phone usage during school hours, citing concerns with students’ academic focus and their mental health beyond the classroom. Four states have restricted phones completely in public schools, and 27 more have active policies, according to Education Week.

At Nueva, the absence of a blanket policy thus far has meant that cellphone guidelines have long been left to the discretion of each teacher. Many verbally prohibit the devices, and some, like I-Lab Engineer Rob Zomber, use door caddies with pockets for students to store their phones before entering the classroom.

A comprehensive set of guidelines will clarify expectations for both students and teachers, an improvement that Upper School English teacher Amber Carpenter looks forward to. “It makes our lives a bit more difficult when we have to be the ‘bad guy’ or the police, and we don’t want to be,” Carpenter said.

Beyond the relief that a defined set of rules would bring, Upper School SEL teacher Sean Schochet looks forward to a policy’s potential to enact real changes in Nueva’s environment, more so than the efforts of individual teachers.

“No matter how strict I am, it doesn’t have the overall impact of students getting their minds less on the phone [and] getting them more anxiety-free from the phone,” he said.

Improving students’ mental health and their connections with each other is exactly why the new policy is being written, according to Bruno.

“Our current desire with the policy is just to have students connect more and spend less time on their phones,” Bruno said.

He added that students’ focus during class isn’t the main concern—it’s the familiar sight of groups of students sitting together but all looking at their respective phones that most worries teachers and administration.

“I look at a phone as an inhibitor of social and emotional [factors], as a human being, and I don’t really care as much about the academic downside,” Schochet said.

And “while it is still socializing,” said Upper School History teacher Simon Brown, referring to phone-in-hand gaming groups, “I don’t think it’s a good way to socialize.”

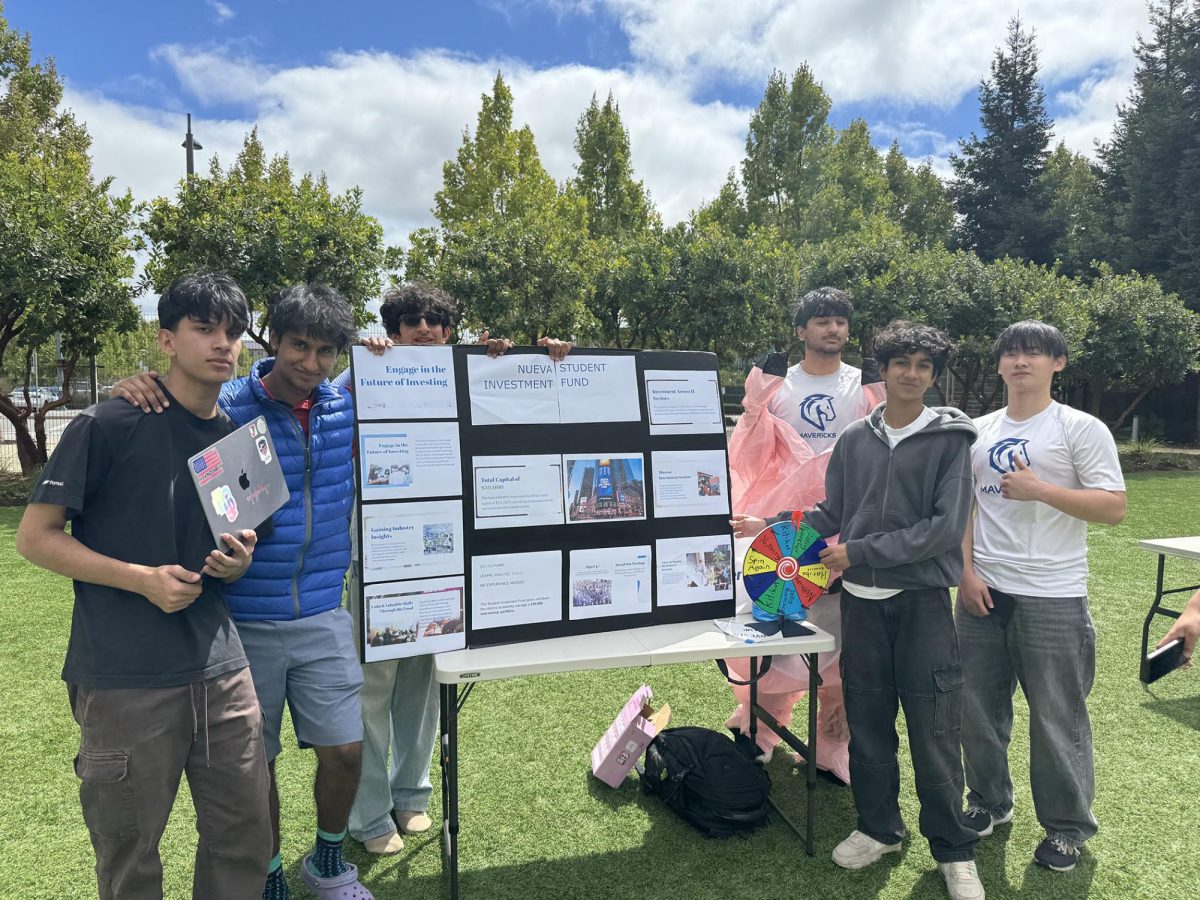

Surveyed about how often they get distracted by their phones in class, 43.2% of 40 randomly sampled students said that they “sometimes” did, and 43.2% said they did not. Despite being cognizant of the potential for distraction—60% said that they had tried to regulate their cellphone usage or implement a self-ban—67.5% opposed the idea of a school-wide policy or ban.

The majority opposition might arise from a resistance to regulations that students like Ritika S. ’28 feel would be unnecessarily strict.

“I don’t really understand why they should police what we do during our passing periods,” Ritika said.

59.5% of those surveyed, though, said they felt their peers were spending too much time on their phones outside of class time.

“We like to tease our friends about that—like, ‘hang out with us,’ right?” Atticus L. ’29 said.

Camilla K. ’28 agreed that a policy would improve her relationships outside of class. “Eliminating phones fosters better discussions, group discussions, when everyone’s not scrolling,” she said.

On the other hand, some students use their phones to check their schedules, plan their commutes on the train, or communicate with their parents throughout the school day. “[My parents] need pretty frequent check-ins just to make sure I’m doing okay, and so having the ability to do that is actually really important to making sure they don’t freak out,” Tate R. ’26 said.

Ritika added that a phone policy would simply not be very effective. “I think that if you’re determined not to pay attention in class, you’re going to find a way to do it even if your phone is banned,” she said. “If you’re a good student, then your phone isn’t really a problem anyway.”

Teachers are aware that students can adapt to a more explicit phone policy by using their laptops. Upper School Chemistry teacher David Eik has begun to be more clear and intentional about times for laptop usage, and he has been relying more on printouts and handwritten assignments.

“All of these are strategies to ensure that we’re all present in the classroom and able to learn together,” he said.

That is the ultimate goal of the new policy, which Assistant Head of Upper School Claire Yeo sees not as a strict set of rules, but as a “philosophical response, with some goals and ways of implementing them.”

College counsellor Paul Gallagher, who still uses a flip phone, is mostly excited for the policy and the environmental changes it might bring.

“I think everyone’s going to be a little bit more interactive. I like the people here, and I want to interact with them more personally,” Gallagher said. “I want them to interact more with each other.”