Senya S. ’26

For most of our generation’s lifetime, its collective name has been undecided. Some floated the Homeland Generation after 9/11, or iGeneration after the rise of smartphones. It was only when the OK Boomer fad of 2019–20 intensified the need for one settled name for the youths to rally under that Gen Z filled the void—a name that meant literally nothing.

The name was an empty mold to be filled with tribal identifiers by the almighty algorithm, but when we look at Gen Z, the cohesion of a single cohort is simply not there. But what could we have expected? This whole idea of naming strictly-defined generations was doomed from the start.

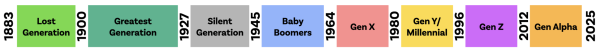

This schema was first codified by authors William Strauss and Neil Howe in their 1991 book Generations, listing American generations from 1584 to the Boomers. Each one grows up in one of four “turnings” (high, awakening, unraveling, crisis) and plays a certain “archetype” (prophet, nomad, hero, artist). The book reads as half history and half astrology, but the general idea stuck.

Strauss and Howe’s descriptors were nonetheless meaningful characterizations (the Baby Boomers were indeed born in a baby boom) but, beginning with Gen X, each name has become increasingly detached from any historical anchor.

Novelist Douglas Copeland coined “Gen X” because he felt the variable x represented a cynical generation uninterested in being defined. But since then, we’ve just kept meandering down the alphabet. Little thought was put into these names or the dates confining them, which was fine for the market research analysts who love nothing more than inventing new demographic cohorts to sell to.

The long-term failure of this approach to generations is seen in the present divisions within Gen Z. Journalist Rachel Janfaza, who covers youth politics, has recently come up with the idea of “the two Gen Zs,” divided by whether you graduated high school before or after the pandemic.

The elder cohort, ending with the Class of 2020, had sharply progressive politics shaped by the Climate Strikes or March For Our Lives. The post-pandemic Gen Z, meanwhile, is the most politically conservative group of young people since the 1980s, with school closures and lockdowns engendering deep skepticism towards the government. This is especially true with young men and boys, but not exclusively.

This dichotomy seems to me like compelling evidence of two separate generations! The recognition of “the two Gen Zs” is a clear admission that the pundits who defined our generation had got it wrong.

Just to be clear, Gen Alpha’s name is even worse. The pitch for this one (again from a consulting firm) was that restarting the alphabet was representative of the first generation born entirely in the new millenium—because nothing says new like the Greek alphabet. Naming and defining the next 26 generations at once was not sociology but a doomed prophecy. I can only pray that we settle on a name with real meaning before it’s too late: call them the Skibidi Sigma generation for all I care, it would still be better than this.

While the most recent generations are particularly potent examples, we cannot give the idea of generations any real descriptive power by just fiddling around the edges.

The movement from generation to generation is far too fluid to have edges at all. Baby Boomers, born between 1946 and 1964, are often tied to the Vietnam War, but many still had baby teeth when the war ended in 1975. The various transformations of sixties America—the counterculture, civil rights, Vietnam—were deeply interconnected, but the people growing up amidst them were never one cohesive group.

Assigning every child to only one generation may satisfy our society’s poorly repressed desire for tribalism, but it requires the categories to be either narrow stereotypes or broad generalities, neither of which is valuable for understanding the members of that cohort. It’s about time we got over them.