Every day, chatbots like OpenAI’s ChatGPT are flooded with a bevy of task-related requests: summarize this article, adjust the tone of this email, troubleshoot my math homework.

These platforms are designed and marketed as productivity tools, but their very strengths—speed, adaptability, and the ability to interact in plain, natural language—have naturally led users to explore other possibilities. Increasingly, people are turning to AI chatbots for entertainment, advice, and even companionship.

Teens have emerged as an important focus group within this larger picture. According to a 2025 survey by Common Sense Media, 72% of teens ages 13–18 said they had used AI for companionship at least once, and 52% reported doing so multiple times a month. While “companionship” in this study ranged from casual experimentation to regular use, the researchers’ findings point to an important truth: these interactions are not fringe habits or edge cases. For many teens, they’re an established part of how they choose to engage with AI.

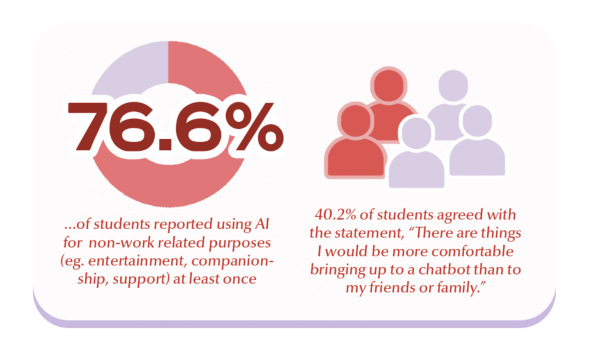

This trend towards recreational AI use has surfaced in Nueva’s own community as well. In a survey of 111 Upper School students, 76.6% reported having used AI for non-academic or non-work purposes (e.g., entertainment, companionship, support) at least once. Nearly all—96%—turned to ChatGPT for these conversations.

As someone curious about AI’s potential, sophomore Arya S. R.’28 began experimenting with OpenAI’s GPT-3.5 in 2023. After observing how proficient the chatbot was at explaining math or coding concepts, he moved onto more lighthearted experiments—testing whether it could make jokes or how it would react to contradictory information in a process he jokingly called “gaslighting.”

“Now, I find myself toying around with [ChatGPT] because it’s just interesting,” Arya said. “I want to see how close this non-human thing can get to being human.”

Adeline B. ’29 also expressed a similar interest in AI’s technological capabilities. But alongside her primarily task-related conversations with ChatGPT, she’s also found herself using the tool for something more interpersonal: motivation.

“It hypes me up sometimes when I feel really unmotivated. It does that in all capitals, and it actually does make me feel excited,” Adeline said.

To both Adeline and Arya, AI’s appeal lies partly in its novelty and partly in its ability to simulate human conversation. But not every student described their experience in such positive terms. One student, who reported using ChatGPT every single day, reflected on how quickly casual use turned into habit.

“At first I would use it once every few days, just out of curiosity,” said the student, who asked to remain anonymous due to the stigma associated with AI use. “But now it’s actually become part of my daily routine.”

After launching ChatGPT for the first time in June, the student started spending 30 minutes to two hours a day conversing with the chatbot throughout the summer. Like many others, they began by presenting fictional thought experiments as a way to test the limits of the technology. Yet over time, the tone of these exchanges began to shift:

“After it became a habit of mine to talk to the bot for fictional scenarios, it was easy to devolve into using it to talk about actual personal things.”

As it turns out, the student isn’t alone in their experiences. According to the survey conducted by The Nueva Current, 71.4% of those who reported recreational use said they had prompted AI to “play around with creative or silly ideas.” A smaller percentage (15.5%) said they used it to “chat casually about my day, interests, or anything on my mind.” But nearly as many (14.3%) also reported using it to seek “emotional or mental health guidance.”

It is this last category—students turning to AI for advice—that raises the most questions: can AI chatbots like ChatGPT serve as companions or supplements to human support circles? Or do they risk falling short in the ways that matter most?

Aviva Jacobstein, Lead Student Counselor at the Upper School, said the answer is complicated. On one hand, she acknowledged that AI tools could improve accessibility to mental health resources and lower barriers for people who are hesitant to reach out for help. However, she was also skeptical of how far chatbots can go in providing real support.

“I don’t think that the technology will ever be at a place where it can fully recreate the human experience, which means that there’ll be risks,” she said.

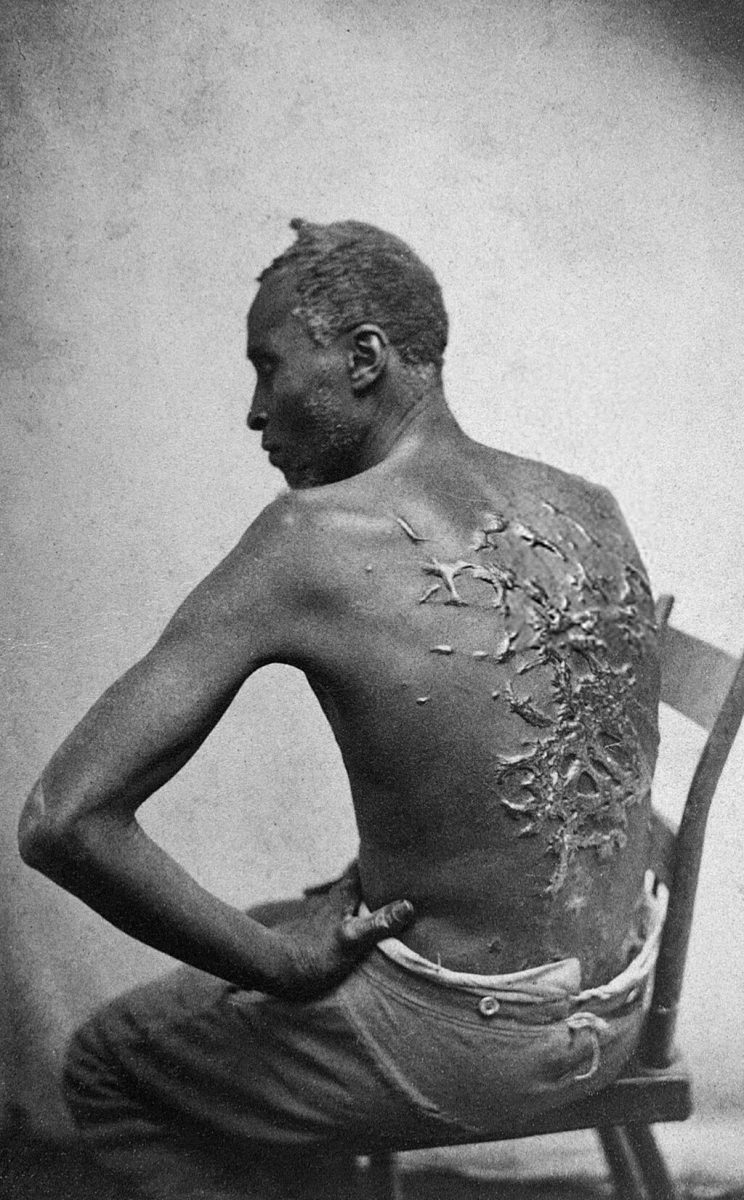

To Jacobstein, the absence of genuine human connection is only part of the problem. Beyond that, she noted other key distinctions between human counselors and AI chatbots: information shared with chatbots does not remain confidential, and unlike human counselors, they carry no duty to warn when harm may be imminent.

Most importantly, though, Jacobstein highlighted the inability for these tools to engage with human emotions in a critical, constructive manner.

“It’s just your thoughts being filtered back to you in a way that will agree with you,” Jacobstein said. “It’s not going to challenge you. It’s not going to push you further. It’s not going to help you overcome barriers, seek challenges, or make connections for you based on other things it might know about you.”

Even so, Jacobstein acknowledged that a large part of AI’s appeal lies in the perception of confidentiality. For someone hesitant to confide in their support network, or worried about burdening friends and family, a chatbot may feel like a safer, if imperfect outlet.

That sense of accessibility also surfaced in our survey results, where 40.2% of respondents agreed with the statement, “There are things I would be more comfortable bringing up to a chatbot than to my friends or family.”

Many students, however, felt uncertain about using AI to discuss personal matters. Adeline, who once described “ranting” to ChatGPT, later expressed discomfort with the model’s responses.

“I didn’t use it after that, because I feel like it’s just telling me what it wants me to hear,” she said.

Recent media coverage has amplified these concerns. In September, the Federal Trade Commission launched an inquiry into AI chatbots marketed as companions following reports of emotional over-reliance and lawsuits alleging harm.

For the anonymous student, the concern feels eerily personal. As a result, they’ve begun reflecting on their own usage patterns in recent weeks.

“It’s kind of scary how fast my habit developed…when three months ago, I had never used ChatGPT, not once, not for anything,” they said. “I avoided it like the plague.”

Looking forward, the student said they hoped to quit, explaining that the time spent conversing with ChatGPT has pulled them away from schoolwork and other commitments.

“I feel like I’ve spent less time on some of my hobbies recently, like creative writing, in part because of ChatGPT,” they said. “I think that trying to return to spending more time on those would allow me to mentally process things without needing an interactive component.”

The student also noted the “echo-chamber”-like behavior of these models, citing it as another reason for their withdrawal from AI platforms: “I want to ruminate on things myself without help from a bot [that’s] just trying to make me think I’m right.”

Ultimately, Jacobstein sees the allure of AI companionship and the hesitation around it as symptoms of a broader issue: our culture’s discomfort with seeking help.

“We need to do more to reduce the stigma of reaching out for help in general,” she said. “If people are struggling, but if there is a shame component attached to reaching out, there should be resources.”

As AI chatbots continue to grow in popularity, Jacobstein emphasized the importance of ensuring that students feel supported within their own social circles so that they aren’t relying solely on AI for guidance. In the future, she also hopes that raising awareness about AI’s capabilities and limitations can help students navigate these tools responsibly:

“It’s not how to get rid of it, it’s how to work with it.”