Chris Scott

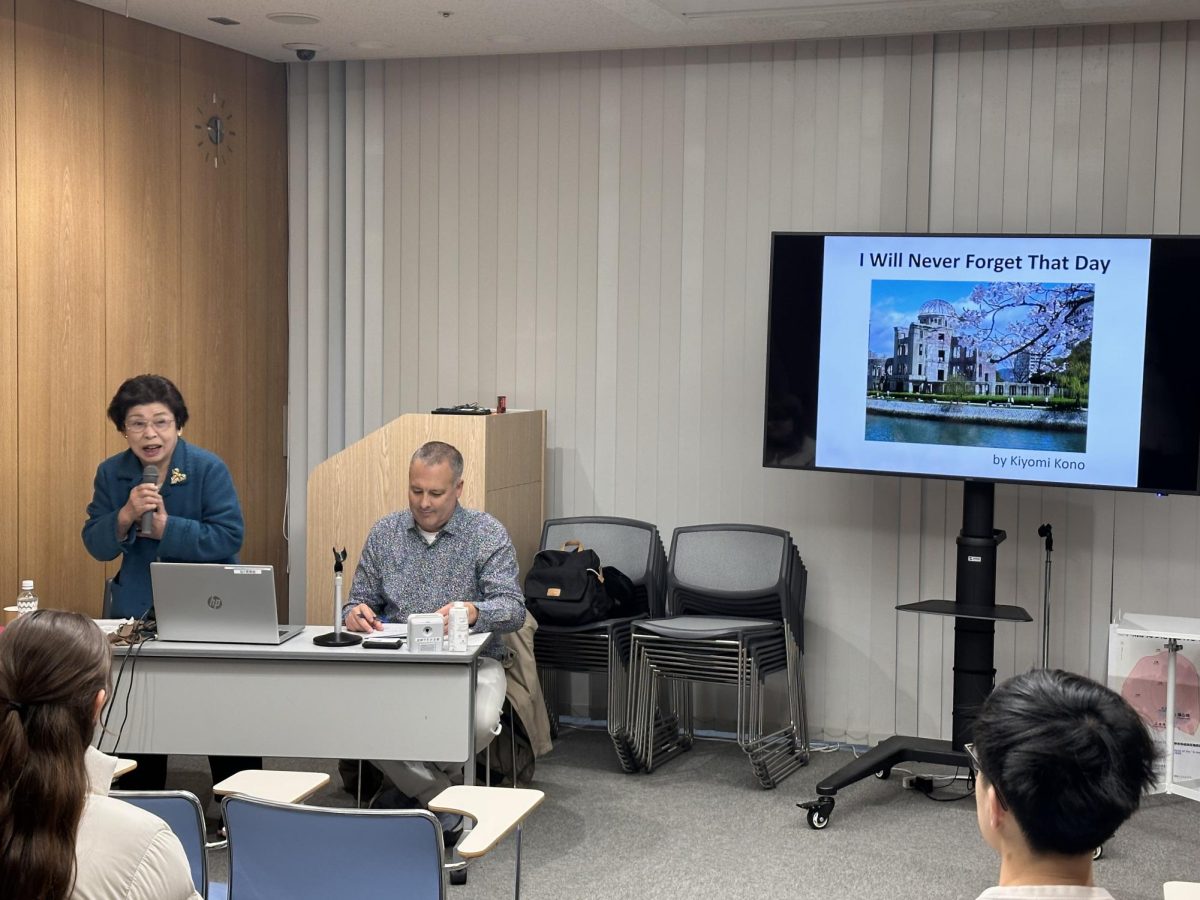

Kiyomi Kono delivers her presentation as Japanese teacher Chris Scott translates.

On Aug. 6, 1945, the United States dropped the first atomic bomb on Hiroshima, Japan. While estimates are still disputed, the Hiroshima bombing took roughly 140,000 deaths by the end of 1945. Three days later, the United States took a similar toll in Nagasaki. A week later, Japan surrendered.

Almost 80 years later, 14 Nueva students, including myself, came to remember the losses the bomb caused.

The Upper School’s Japan exchange program is about to celebrate its tenth anniversary next year. The program connects Nueva students taking Japanese across skill levels with students at Doshisha Schools in Kyoto.

After attending school with our exchange students, Nueva students spent the final three days of the trip exploring Japan as a group. The final day of the trip was the somber visit to Hiroshima, where America dropped the first atomic bomb that brought World War II to a close.

The memorial museum at Hiroshima is exceptionally well done. I believe it is an obligatory visit for any American with the chance to go. This museum concerns itself less with the big-picture view of the war, where individual people’s tragedies become nationalized statistics, but instead painfully recalls the devastation and breaking of hundreds of thousands of families.

This museum moves you to tears. There are only so many burnt and warped personal belongings, only so many letters to family, and only so many untreatable chronic illnesses, that one can process. It is a memorial to the parents left childless and the children left orphaned.

The most striking experience that day was meeting with a hibakusha (survivor of the atomic bomb). That morning, we heard from Kiyomi Kono, who shared with us her story and drawings of venturing into Hiroshima the day after the bombing to find her two sisters, who both survived.

Kono, who is 94 years old but to my eye looks no older than 70, has now spent decades telling her story at colleges and museums across the world, working to ensure the bombings are never forgotten. It is a personal legacy I marvel at.

Survivors of Aug. 6, 1945, went through indescribable losses and unspeakable pains that lasted the entirety of their lives. What I am most in awe of, then, is the way that the community of the bombings’ survivors (about 100,000 hibakusha still survive today) have spent the past eight decades working towards the abolition of nuclear weapons and the creation of peace.

The extraordinary rebuilding of Hiroshima was truly something to behold, and we can only hope this community’s lasting wish—“No More Hiroshimas”—will be granted by the future generations obligated to remember it.