Part I: Traversing wealth in and out of the classroom

The annual Book Fair was in full swing, and Brenna A. M.’25 was excited. She rushed to a friend and told her about the $30 they each had in their Nueva accounts for purchasing books—a benefit for students who receive financial assistance. Her friend was resistant.

“I told [my friend] we should go over and use the money and she said no, because it was too embarrassing for her,” Brenna said. “She said, ‘I don’t want to tell them I have the money because I’m on financial aid.’”

While students do not need to actually reveal their financial assistance status to use the money during the Book Fair, the real discomfort with using those funds still remains, a pervasive feeling that goes beyond this one experience.

Nueva’s financial assistance program goes beyond tuition; the school covers the cost of additional programs and services, generally at the same percentage of the financial assistance families receive. This can range from transportation, athletics gear, opt-in electives and activities, senior prom and senior yearbook pages—to spending money for overnight trips, college application fees, and standardized tests taken at Nueva. The goal is that “every Nueva student can take part in the full Nueva experience.”

Yet, students who are entitled to these benefits can experience discomfort around using them. Students appreciate that they’re available, but may also feel sensitivity, shame, or embarrassment.

These moments are shaped by class consciousness, the self-understanding and various beliefs around personal socioeconomic status—on its own and in regards to others. It can materialize as embarrassment around receiving financial assistance, or, conversely, self-consciousness around having privilege. It is shaped by how wealth is generally discussed—or not discussed—as well as the overall distribution of wealth and privilege present.

Nueva is located in the Bay Area, one of the most expensive areas to live in the country, where the gap between affluence and economic vulnerability is wide. The student experience at Nueva includes two beautiful campuses and facilities, state-of-the-art labs and maker spaces, yearly trips, and modern technology and software; these benefits are reflected by both a significant tuition ($59,720 for the Upper School in 2024–25) and a generous community that supports the school through annual fund giving.

In the Upper School, students come from a range of socioeconomic backgrounds, zip codes, and middle schools.

For the admissions team, understanding andFor the admissions team, understanding and accounting for these differences in the applicant pool begins with transparency. Director of Admissions Melanie León noted how affording a Nueva education is an open conversation from the very beginning of the admissions process.

“In [all panels and information sessions], I’ll introduce our financial assistance program so that prospective families with limited financial resources won’t immediately feel the need to rule out the school,” León said. “Instead, our hope is that they can go through the self-selecting process to think about whether Nueva would be a good fit.”

Concurrently, in THRIVE, a program for students from historically underrepresented backgrounds—which may include students who qualify for a certain degree of financial assistance—explicit talk of wealth and privilege might emerge. Some of the group’s conversations are in the context of adapting to class differences new to students.

“If this is your first time in a private school environment, it’s definitely a different world,” said Director of Equity and Inclusion Shawn Taylor. “I think that you have to become fluent in all the nuances of that community to feel like you’re a part of it.”

Various Nueva initiatives also seek to provide equal opportunities for all students. For instance, the Internship Program, available to all 10–12th graders, increases access to internships that might otherwise require a connection or referral. Students who receive 50% or more financial assistance may also receive wages for a paid internship through Nueva—even if the employer does not pay for it.

“What Nueva has done is try to provide support in all aspects of the Nueva experience so that students receiving financial assistance never have to shy away from participating in something because of the cost of it,” León said. “I think that can move us forward in terms of hopefully taking anxiety away from being a family who receives financial assistance.”

The financial assistance program serves 195 students across the three divisions, roughly 20% of the student body. With approximately 7.5 million dollars committed to the financial assistance program for the 2024–25 school year, support varies greatly.

But beyond just being able to afford a Nueva education, the reality of what it means to be a student receiving financial assistance can be felt in the social fabric of fitting in.

Whether it’s being able to call an Uber to weekend hangouts or choosing the restaurant for a meal, there are plenty of social interactions where the socioeconomic differences between peers become more apparent and keenly felt. These aspects are not strictly school-related in the academic sense, but are still a part of one’s experience as a Nueva student.

Brenna believes that the observed socioeconomic differences are not inherently bad, nor worth hiding.

“At the end of the day, I don’t think that it matters as much as it seems,” Brenna said. “I think there’s a lot more worries about judgment than actual judgement around class.”

For Gemma M. ’28, her worries around being judged are reflected in her unease in situations where her socioeconomic status may be revealed. She described the apprehension she occasionally feels when being driven to school by her older sibling.

“Our car is not the most flashy—it sometimes makes a noise when you turn,” Gemma said. “I know it doesn’t represent me and that it’s just a vehicle I’m in. But sometimes when I go to extracurriculars, even though I know I shouldn’t, I’ll ask to be dropped off farther away.”

Wendy E. ’26, a student on financial assistance, believes that this unease may be related to a general discomfort around entering a well-resourced private school environment like Nueva, which can be a uniquely self-conscious situation for first generation college and/or low income (FGLI) students.

Having come from a different middle school, she noted how some of the privileges her peers possessed seemed bewildering at first.

“As a student on aid, [I know] it’s easy to feel unfit here because you’re not as wealthy as a lot of your peers. But then going back to your normal socioeconomic environment, you might also feel unfit because you’re still getting these privileges and opportunities from a wealthy place like Nueva,” Wendy said. “The back and forth kind of creates a paradox [of] who you actually are.”

For Aiken C. ’27, a student on financial assistance who joined in sixth grade, moving between vastly different socioeconomic environments has made him more fluent in code-switching; the differences in his behavior manifests in the way he talks about money. With old friends from the public school he attended before Nueva, he will casually reference his socioeconomic background and upbringing in conversation. At Nueva, he simply does not mention the subject.

“I try to keep away from it—not because I think that people won’t understand or because they’ll be snobby, but because I can’t relate to them as much about it,” Aiken said.

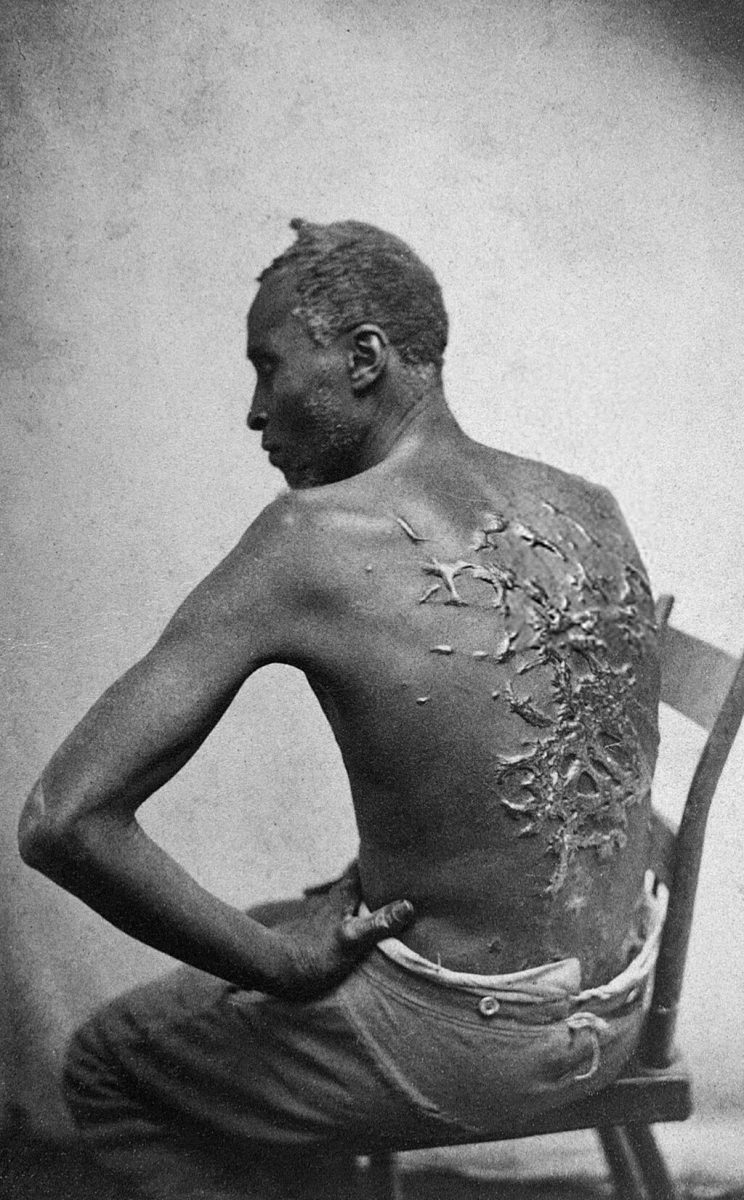

The reluctance of students to reference their class is not just a result of self-inflicted judgment—insensitive or presumptuous comments have also shaped their discomfort. Aiken recalled hearing peers refer to poor San Francisco residents as unintelligent and drug-addled at school.

“As someone from a less well-off city neighborhood, it hurt,” Aiken said.

Wendy has faced similar moments of discomfort, such as when she heard peers laugh about kids they were tutoring as part of Peninsula Bridge, a local organization that helps first-generation, low-income students to achieve college and career success, then refer to being a TA as an experience purely for listing on a resume.

“I am part of Peninsula Bridge,” Wendy said. “I’m very much one of the students that you could have been helping.”

Another time, she recalled mentioning how she wasn’t sure if her financial assistance covered trips expenses—and if so how much—to a friend. A peer overheard and remarked, “Oh, so I’m basically paying for you, then?” Wendy was not sure how to immediately respond.

For Aiken, these kinds of comments are difficult to call out, given the lack of any overt malice.

“I’ve never heard someone being made fun of for being poor. It’s more comments with these undertones,” Aiken said.

Still, no matter how subtle, comments create culture. Uncomfortable moments inform conversations and the reluctance around talking about financial assistance, and extend towards shaping the way wealth and privilege is generally discussed.

Upper School Head Liza Raynal has heard various jokes about the privileges students possess (such as multiple properties), in the form of casual teasing between friends with a self-deprecating tone.

“Jokes are good in that they diffuse tension. But I think jokes don’t allow for the nuance of how complicated it can be to be able to be here,” Raynal said.

Miriam H. ’27 has observed how jokes that reference supposedly wealthy individuals become gossip, with a similar lack of nuance.

“People’s wealth is talked about more behind their back than to their face. I’ll hear whispers of, ‘oh, this person’s really wealthy.’ It becomes a character trait, almost,” Miriam said.

Ayaan M. ’26 has noticed similar conversations—as well as the possible causes for the rumors: his peers’ casual mentions of international weekend trips and luxury cars.

“ I know people that will say, ‘oh yeah, I just did X and Y for the weekend,’ or ‘just went to X on vacation and bought all this,’” Ayaan said. “I’m made well aware of people’s privilege and wealth when they talk about their life.”

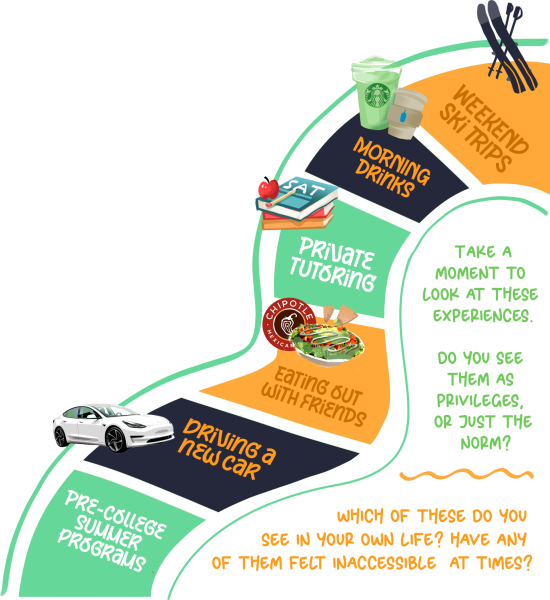

Ayaan emphasized how these mentions of privilege are not intrinsically adverse on their own. However, their constancy can impact whether expensive possessions or experiences are considered to be privileges, or normal.

Evan W. ’26 described a custom he’s seen with many of his peers, where students will buy or be gifted a brand new car immediately after getting a driver’s license. As Evan went to a public middle school with students from mostly middle-class backgrounds, he was surprised how his time at Nueva made the phenomenon seem almost ordinary.

“From some of my friends who are a bit older and go to other schools, I know this is not something that happens really outside of here,” Evan said. “But you wouldn’t know that at Nueva. I get to school and see the cars, and I feel like it’s normal after three years here.”

Evan’s experience speaks to the broader expectation of wealth, which many students have noticed, regardless of their socioeconomic background and how long they have attended the school.

Nathan S. ’25, coming from a public elementary school and private middle school, wasn’t quite sure whether to expect students with similar socioeconomic status or not, as well as what the overall wealth distribution would be like. This uncertainty was quickly amended.

“Once I walked through the doors, I got the general impression that everybody was of a higher socioeconomic class than me,” Nathan said. “Then again, because people don’t really talk about it, I’m not sure how accurate of an impression I really have.”

Some students attributed these impressions to a lack of conversations that explicitly address money, even in contexts where the subject emerges naturally.

Aryan M. ’25 described the cyclical nature of how a discomfort to discuss money and assumptions around wealth interact.

“It’s tough because of our general community demographic and the fact that we are a private school,” Aryan said. “If everyone thinks everyone’s coming from the same rich background, school can become an environment that doesn’t exactly encourage talking about [wealth].”

In the times where wealth or socioeconomic differences have come up, Aryan has found value in addressing them with his friends. He characterized the conversations as generally illuminating, but rare.

Nathan’s experience has vastly differed from that of Aryan’s. The few conversations Nathan has noticed were completely private, often occurring between close friends. Still, whether discussing fees for a concert or gas for a road trip, the atmosphere was somewhat uncomfortable.

“In my experience, it’s something that people avoid talking about,” Nathan said. “It can get awkward when it’s brought up.”

In that awkwardness, there is the potential for hurt—especially alongside the intersection of privilege, assumptions, and shame.

Ayaan noted how it can impact social lives, pointing to activities that require significant expenses, like a trip to TopGolf, or eating at the mall after school every day.

“ Classism at Nueva is not necessarily malicious: it’s subtle, and can be exclusionary. There’s a price tag to some interactions, and we’re not always as mindful or accommodating as we could be,” Ayaan said.

Part II: Redefining the conversation

Patrick Berger, economics teacher and 9th grade co-dean, has made a conscientious effort to have frank conversations around privilege and wealth with his students.

During a recent advisory, a conversation about the future devolved into worries about getting a job without some specific college acceptance. Berger eventually suggested his advisees think about the privileges implicit in those worries.

“I got pretty exasperated after 20 minutes of these kids telling me, ‘my life will be over if I don’t go to Harvard,’ and ended up just telling them to look around at the environment they’re in,” Berger admitted. “Because even if we deny it or don’t talk about it, this place is a powerful network into positions of power and privilege for any high school student to have.”

Berger characterized his tone and the conversation as unusually blunt. Typically, he might make a lighthearted joke about Nueva privileges and resources students have seemingly grown accustomed to, or embed issues (such as rent control, or long-term environmental concerns in low-income neighborhoods) into his lessons that might not be immediately relevant in students’ lives.

“I was able to start a conversation this time because I’m very comfortable with these kids. But it’s such a tricky subject to navigate as a school,” Berger said. “If people walked around advertising their income status and the donations their parents made, that would be [odd.] And if they walked around with absolute silence and denial about either of those things, that would also be strange. Where do you find that balance of respect and acknowledging privilege?”

Director of I-Lab Angi Chau has attempted to find that middle ground. As a Nueva parent, she has encouraged her son to remember his audience and think about intentionality in talking about nice gifts or trips with his friends.

“There’s a difference between sharing cool things in your life and flaunting your privilege that I try to have an intentional conversation with him about,” Chau said. “We talk about, how do you think what you want to share might make your friends feel? Might it make anyone feel sad or left out?”

Yet, Dean of Students Jackee Bruno also emphasized how socioeconomic differences are something that students will be expected to encounter.

“In college, navigating the diversity of my friends and peers’ backgrounds was important,” Bruno said. “And in my life now, it’s still relevant.”

By acknowledging these disparities in high school, students get a chance to learn to navigate them with appropriate respect and tact.

Instead of trying to hide or be self-conscious about privilege, I-Lab Teacher and 12th Grade Dean Morgan Snyder highlighted how moving towards action can be meaningful, especially in a new environment where work around reconciling privilege can occur.

“I want my students to not get stuck in that self-consciousness about privilege. Instead, I like to say: What will your piece of service look like?” Snyder said. “Go out there and learn from people who have actually been working on those problems for a long time. Because teachers [on their own] can’t help you translate an intention to do good or an understanding of systemic injustice into actual action.”

Meanwhile, history teacher Tom Dorrance, who is also a Nueva parent, expressed concern over how an absence of teacher guidance may contribute to an unspoken assumption that every student is wealthy.

“I think, as staff, we keep class in the shadows because we don’t want anyone to feel bad about their class status,” Dorrance said. “But perhaps we almost implied that then students shouldn’t talk about their class status, and made financial assistance or a working class experience something to hide—rather than just a reality that is just as normal as being in a position of privilege.”

To combat such an implication, Dorrance suggested setting up a basic familiarity with language regarding class and inequality.

“We’ve learned some vocabulary on what it means to be an upstander or ally, and talking about microaggressions. But we just don’t have that toolbox to talk about class,” Dorrance said. “If this is a subject that we really want to start taking on, I think we’ve got to start there.”

To Ayaan, there is no perfect, systematic solution to prevent every inconsiderate comment or awkward moment. Rather, he believes focusing on the interpersonal aspects of the issue is where real change can occur.

“As people, perhaps we just need to talk about privilege and wealth more,” Ayaan said. “And in those conversations, we should be more mindful and think about the fact that one fifth of us are on financial aid, and the implications of that.”

And if that mindfulness falters, Rohan K. ’26 has some suggestions. As a student receiving financial assistance, he has generally been frank with his friends and peers about that fact throughout the seven years he’s attended Nueva. Although the matter has typically been met with support, he has also learned how to mitigate any uncomfortable moments.

“If someone judges you for being on aid, then maybe you don’t want to hang around that person anyways, or maybe you try to have a conversation and call them out,” Rohan said.

In a similar vein, Brenna has refused to be ashamed about being on financial assistance. She has developed her own simple approach to mitigating any embarrassment for herself or others.

“You can’t change what other people think, you can only really change your feelings. That’s my philosophy,” Brenna said.

Taylor believes that accountability is key to building a better community overall. He hopes to build up a baseline level of comfort for being gracious and firm with asserting boundaries around any insensitive comments or judgement that comes up.

“Let’s be okay with saying: We don’t do that in our community here,” Taylor said. “At the same time, it’s okay to [make mistakes] and be raggedy as long as you’re not being mean.”

To Taylor, balancing accountability with allowing people to fumble and be awkward fosters an environment that welcomes dialogue. Paul Gallagher, 11th grade dean and Associate Director of College Counselling, similarly emphasized the importance of being comfortable with the uncomfortable moments that may emerge.

“Whenever you’re in a diverse community, I think it’s inevitable that some people’s boundaries are tread upon. But I hope that there is a strong enough foundation of trust and grace that people feel [equally] comfortable calling someone out or apologizing,” Gallagher said.

Some students have already started to do so, simply by opening up the conversation around money. In getting more comfortable with the subject, students can become more comfortable with each other, and build that foundation of trust.

Recently, Nathan’s friend group discussed finances for their senior trip, a conversation that made them explicitly address socioeconomic differences.

“There is a diverse range in terms of what people can and want to spend [on our trip]. Now that’s been something that took us a while to talk about, but there is real use to these conversations,” Nathan said.

In addition, Rohan’s open approach to financial assistance is another step towards shifting the culture—though he acknowledged the very real worries other students receiving financial assistance may possess.

“I get that having people know is a scary thing,” Rohan said. “But I think we should at least feel more comfortable [talking about it]. Maybe it sometimes seems like no one else is on financial aid, but you’re really not the only one.”