Opening Article:

Collective pronouns to refer to American nationality—we, us, our—sounded just a little bit different the day after the election; more resonant for the winners, more fragile for the losers. The results were concrete, official confirmation of how “we” do not all view “our” country the same way and are split between party coalitions backing deeply polarized candidates.

Republican candidate Donald Trump won with a decisive 312 electoral votes and 49.9% of the national popular vote, while Democrat Kamala Harris conceded the race with 226 electoral votes and 48.4% of the popular vote.

The election invites in its aftermath a consideration of what it means today to be an American and belong as an American.

As history teacher Tom Dorrance framed it for the school community, belief in the very democratic process that revealed Americans’ differences is core to the national identity. Dorrance delivered a speech entitled “On Democracy and Democratic Values” at the all-school assembly the day after the election, and faith in democracy and in common humanity came across as central themes.

“Freedom has been a cornerstone to what we consider American identity, and I think we associate freedom with democracy,” Dorrance said.

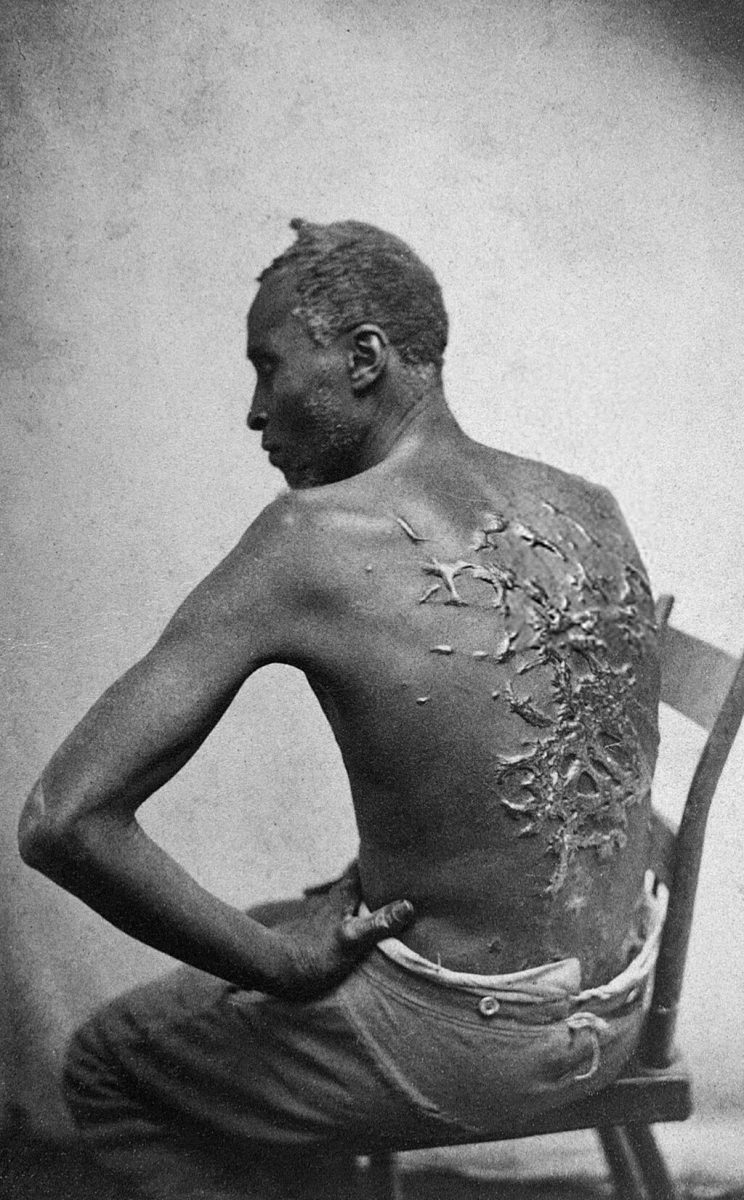

Conflict over freedom, however, is a consistent pattern in U.S. history. Dorrance argues that supposed efforts to secure an in-group’s freedom have often involved oppression of an outgroup. Nativist prejudice toward immigrants offers both an ongoing and long-running example.

“The starting point for understanding [American identity] is as something that is contested, and something that people fight for recognition of and fight to deny recognition of,” Dorrance said. “That struggle, I think, lies at the heart of understanding American identity.”

Campaign rhetoric for the election aimed at cultivating voters’ belief that the candidate and party recognize their citizenship in more than a legal sense. Under a longstanding atmosphere of, in Dorrance’s terms, “citizenship as part of a contest,” voters may seek affirmation that their identity places them as the heart, the everyman, or the backbone of the American people.

Broadly, in Dorrance’s analysis, the Republican movement’s successful appeal to voters estranged by cultural politics calls back to an idea of the “real America” posed by the 2008 John McCain-Sarah Palin campaign. Palin’s rhetoric championed small towns over cities and pitted patriotism against cosmopolitanism. Trump’s approach runs along similar lines.

“In my perception of the way in which they talk about themselves, is that [the Trump movement] is speaking up for—and I’m going to be intentionally gendered with this—the forgotten man,” Dorrance said.

Although far from the only relevant window to consider political movements, the election prompts recollections of how time and again, Americans have refused to accept exclusion or underrepresentation and instead pushed for freedom and willed the country to become more democratic. In and of itself, Americans’ pursuit of recognition for their rights and privileges as citizens is an expression of national identity.

“Dissent is as much a part of our tradition as acquiescence to the status quo,” Dorrance said in his Nov. 6 speech. “When you look at that mirror reflecting our national culture and don’t recognize what you see, that does not mean that you don’t belong and it certainly does not mean that you need to stay silent.”

In the weeks following the election, community members have looked into that “mirror.” They considered how the election reframed the country in their eyes, what they associate with American identity, and what American identity means to them now.

Gavin Bradley

College Counseling

In the office of Director of College Counseling Gavin Bradley rests an American flag, folded into a triangle to resemble the tri-cornered hats worn by soldiers who fought in the Revolutionary War.

For Bradley, a veteran of the Marine Corps, the flag symbolizes his time in service and his pride in being an American.

“I love America, and I have my version of patriotism that I express—I get teary at the national anthem in the right setting and I tell people that the Marine Corps is the best branch of the military,” Bradley said.

Bradley has also spent much of his life defying the stereotypes associated with someone of his background and identity. As a self-described “cisgender White man from the South,” he believes that people falsely assume he holds conservative views.

“A lot of people with my résumé would be conservative,” Bradley said. “So I often make an effort to present myself in ways that contradict those assumptions.”

Bradley believes that immigrants are central to the identity of America. He is critical of the current political trajectory as one that wrongly “vilifies immigrants,” but believes that America will return to being a more inclusive country.

“When you talk about these sorts of larger issues, there have always been [political] pendulum swings. But, we’re fundamentally a country made up of people from other places,” Bradley said. “I think the problems of deporting a lot of people will be revealed rapidly and we’ll find a different way to be more inclusive. The pendulum always swings back.”

After the recent election, Bradley tried to refrain from a “defeatist” attitude and encouraged his three children to do the same.

“Nothing is ever as good or as bad as it seems even in that moment,” Bradley said to them over a text message. “It’s hard not to imagine the worst outcomes happening, but we need to not be defeatist. Be smart, be brave, be safe and have hope.”

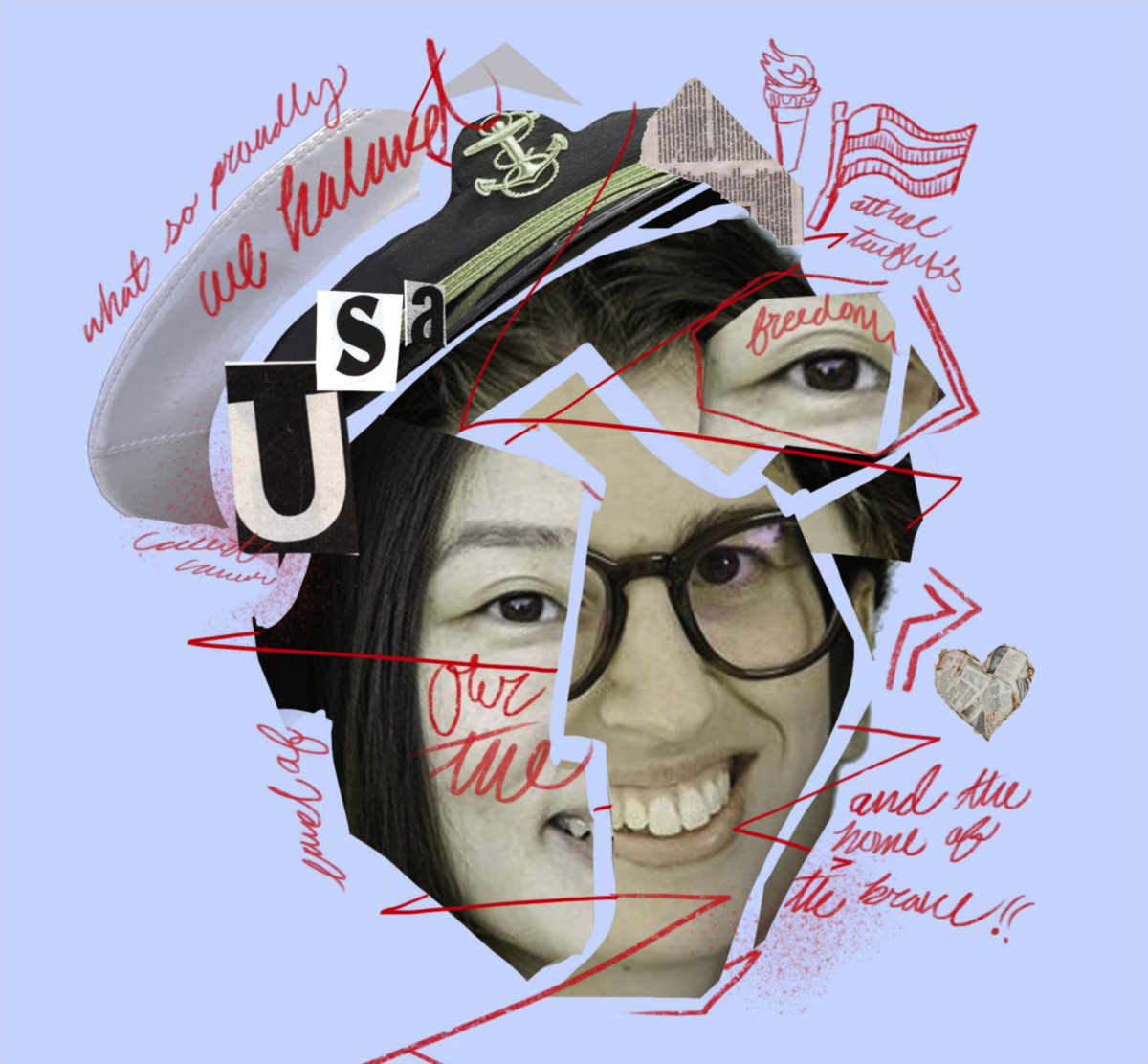

Joshua Byun ’23

Alumnus

*The views expressed by Joshua Byun are his own and do not reflect the positions of the United States Naval Academy or any branch of the U.S. military or government.

Alumnus Joshua Byun ’23, now a sophomore at the United States Naval Academy (USNA) with plans to work in cyber warfare, did not share his political opinion with classmates on Nov. 6 when Donald Trump was elected the nation’s 47th president, nor in the weeks before and after.

Students of the USNA are prohibited from engaging in partisan political activity by the Uniform Code of Military Justice. Byun believes that this practice of political impartiality is critical.

“Keeping an apolitical military makes sure that the military is subservient to civil leadership,” Byun said. “If the military acted as a separate political institution, like in British history when the Monarch had the army fighting on their side, we couldn’t have a democracy.”

Byun has “always wanted” to serve in the military, in part inspired by conversations with veterans he’s had at school and through extracurricular activities. He describes Marine Corps veteran Director of College Counseling Gavin Bradley as a “mentor” who taught him about service, and gained confidence in choosing the Naval Academy after talking to Air Force veterans John and Susan Feland, parents of Anna Feland ’24.

“I want to help other people. The military is a good first step for me to join something larger than myself and try to make a difference,” Byun said. “At the end of the day, we’re all on the same team.”

Davis Dietzen ’25

Alumnus

Trump’s election may signal a deepening divide in American politics, but Davis Dietzen ’25 finds himself on neither side, increasingly disconnected from both the Democratic and Republican party platforms.

“I see this split happening and I’m sort of hovering in the middle of it,” he said.

Eastern Orthodox Christianity is a core part of Dietzen’s life that neither party has outspokenly claimed to represent. He considers his religion separate from, and more valuable than, his national identity.

“I definitely acknowledge I’m American, but when I think about my identities, my cultural and religious identities are more important to me,” Dietzen said.

While Christianity takes priority, he does feel close ties to his country when he is together with family members who have been involved in the military and government.

“When I’m with my family, I remember my personal connection with America, and that does make me feel more strongly about being American—more proud of it,” he said.

History classes also prompt reflection on the United States’ image. There are times Dietzen thinks “this is awesome” and others when he is “upset” or “confused.” In an academic setting, though, he primarily takes a removed, third-person view of the country.

When politicians call out to American voters’ races, classes, and creeds, Dietzen cannot fully hear his identity knowing his religion is excluded.

Hunter S. ’27

Nueva Student

After the election, Hunter S. ’27 called his mom and grandmother to talk about a myriad of topics—women’s rights, queer rights, the “Muslim Ban.” In the aftermath, he was left with feelings of disappointment, failure, and fear.

“[This election] has made me lose hope, given how many Americans agree with [Donald Trump]. It doesn’t feel like they have the same values, or even the American values,” Hunter said. To him, it feels as if the United States no longer stands for the Constitution and America.

For Hunter, one of the most important parts of living in the United States is its First Amendment. “One of the things that makes me feel American is having appreciation for freedom of speech,” Hunter said. “I have a lot of strong feelings about things so I think that’s a really valuable part of being an American.”

There are many issues that Hunter feels pessimistic about, both in retrospect and for the future, but he does feel hopeful. “I’m feeling optimistic that this will bring people together so we can all fight for what we want and our rights,” Hunter said.

Rohan K. ’26

Nueva Student

Until he was 10, Rohan K. ’26 lived in Knoxville, the third largest city in Tennessee. Since moving to California, he felt as if his [home] state was a place he could visit, but in more recent years those feelings have shifted.

“I’ve talked to some of my friends there who have noticed this huge change in how things are there,” Rohan said. “You have to be very careful with what you say. We didn’t feel that safe place to go and visit like it used to be.”

Living in California now, Rohan feels he can express his political opinions openly, with those who share his stances or not. “I feel like I can have a conversation with anyone, whatever they believe in, and it would be respectful. I would learn something, we would talk it out,” he said.

Rohan still feels uncertainty about the results of the election, but remains hopeful. No matter what the next few years bring, what he believes is a benefit of this election cycle is his growing interest in politics. While Rohan is not old enough to vote, he began to think more critically about the political environment of the United States. “I was talking about the election a lot more, learning about the election a lot more. I’m interested to learn and see what’s going to happen,” he said.

Regina Yoong

English Teacher

Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, the city that Regina Yoong, Upper School English teacher, grew up in was a “mix of Malay, Chinese, and Indian cultures.” Yoong learned English, Malay, and Mandarin at school, and was surrounded by Islamic culture; her childhood experiences are that of multicultural values and beliefs.

Yoong received a Fulbright Scholarship to attend graduate classes in American literature at Ohio University while teaching Malay. Living in Athens, Ohio, one of the poorest counties in the United States, was an eye-opening look into the struggles of Appalachian communities, a part of the United States she had not known.

Despite the mild discrimination Yoong faced there, she remained steadfast about her origins. “You can be ignorant of my culture, but I will continue to tell you my story and history,” she said.”

In Malaysia, where Yoong’s parent’s live, freedom of speech is not guaranteed. “In Malaysia just critiquing an opponent, especially a person in power, is not something that’s acceptable. You might be jailed or investigated,” Yoong said. “Sometimes people don’t see the value of the freedom of speech and [will] just say things and not take responsibility… But what I’m saying is that freedom of speech is a great thing, and I love that we have it here.”

Growing up in Malaysia and living in various regions of the U.S. has helped shape Yoong’s values. “I still have a lot to celebrate about American democracy, and I see things as a model that every country can look up to,” she said. “American democracy is a great thing, and I think it values an individual for who they are, no matter how different they are.”

After living in the United States for ten years, Yoong is on the path towards becoming an American citizen. “Where is home?” is what Yoong asked herself. “Home is very much still in Malaysia, but my immediate family: my husband, my daughter, they’re here. They’re American citizens, and so home is also here.”

Yoong acknowledges the uncertainty of the coming years, and what unknowns they might pose. Drawing from her experiences, she feels optimistic about what American democracy and values stand for.

Paloma Fernandez-Mira

Spanish Teacher

Paloma Fernandez-Mira, Upper School Spanish teacher, spent her childhood and most of her college years in Northern Spain. Her first time living in the United States was when she was a high school student studying abroad in North Carolina, then later, as a college student in Boston, Massachusetts. Now in California, Fernandez-Mira acknowledges her different experiences living in various parts of the country.

“My life was very different in all those different places [but] I always felt like the people were super warm and open to getting to know someone that was very different. They were very generous to show me everything about their country,” Fernandez-Mira said. “I’ve always felt very supported, [that] it’s okay to be different. I think that’s something that the US really shines in; the diversity and the acceptance of difference.”

In regards to the 2024 election, Fernandez-Mira feels separate from American politics. “I’m not a very political person. I was more interested or worried about my own situation in relation to immigration, because my family and I are going through the immigration process. I was just trying to observe and listen to everything that was going around me,” she said.

For Fernandez-Mira, she directed her energy towards the Nueva community, acknowledging that elections can feel especially intense. She encouraged her community to be open-minded and not judge individuals with different views or beliefs.

“I think it’s important to not put a label on someone…but really try to understand everyone,” Fernandez-Mira said. “In the case of people that have a story related to immigration in this country, it’s really a whole different view…so it’s also important to understand them.”

Anna Aganina ’25

Alumnus

Anna Aganina ’25 has developed a view of American identity that is defined relative to her parents’ experiences in the former Soviet Union and confirmed in her personal experiences.

“It’s the ability to exercise your freedom within the capacity that this country has for us,” Aganina said. “My parents came here because they wanted to have freedom of choice, because they came from the communist Soviet Union. The way they raised me was: to be an American means you have more freedom, more individuality, and more free will.”

Aganina’s mother was born in Kiev and her father near Moscow. Aganina and her brother, Misha Aganin ’23, were both born in the United States and carry dual U.S.-Russian citizenship.

Growing up, Aganina interacted with American nationalism at the public school she attended. Each morning, she sang patriotic songs with her class like “America the Beautiful.”

In high school, her understanding of American identity has solidified in history classes, both through the content and the opportunity to think critically about the country’s past and its echoes.

“[In class] when we see a lot of rallies and protests and movements, I feel this sense of agency that we have in the United States,” she said.

She feels most connected to the country when she gets to witness the democratic process.

“During times like elections, having the ability to see my country evolve, and see the people around me have the agency to vote and have a say,” Aganina said.

After the presidential election, she and her family are concerned, based on the campaign messaging, that Trump and his administration will speak on behalf of others’ rights. For Aganina and her family, the preservation of individual agency and democracy are essential to maintaining the national character that drew them here a generation ago.