Part I: Great Expectations

A day in the life of a Bay Area teenager in 2025: Since you were eight, it has been your dream to go to school on the East Coast and attend an Ivy League university. You are aware that many of your friends share these dreams. You have straight As, over 100 hours of community service, and are a two-sport athlete to balance out your academics. You know one classmate recently participated in a national debate competition, and you know another started their own non-profit organization from scratch. You worry if you have done enough to stand out. And there is a reason you feel this way.

Specifically at Nueva, data from the College Counseling department shows that 35% of students from the classes of 2017–2020 and 36% from the classes of 2022–2025 attended highly selective schools with admissions rates as low as three percent and regularly top the Best National University Rankings from U.S. News & Report.

A side effect of these matriculation results has caused ripples among the student body. Some find that the consistency of high acceptance rate to highly selective universities of prior years breeds lofty standards.

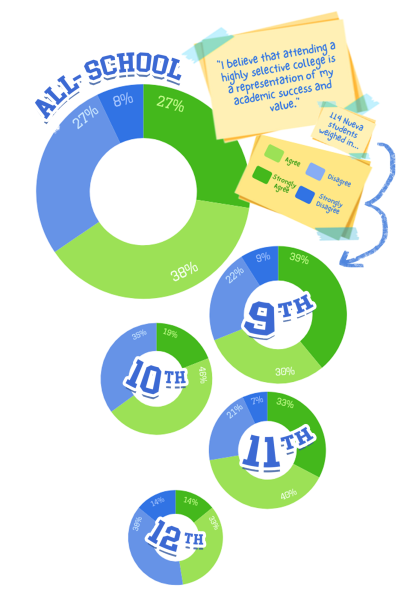

In a survey given to 113 Upper School students—roughly a fourth of the student body—the data shows that 88% of freshmen, sophomores, and juniors agreed that it was important for them to attend a highly selective college, and 69% agreed that attending one would be representative of their academic success and value.

One freshman wrote on the survey, “[If I didn’t], I would feel like going to Nueva was all a waste.”

The underlying pressure expressed in the survey does arise from some students sharing the same college goals—and feeling like they are in competition for a limited number of spots—but external factors also influence it. For example, social media plays an outsized role in amplifying these feelings of competition by constantly showcasing peers’ achievements, college acceptances, and curated academic successes.

In mid-May, Nueva seniors gathered on the Rosenberg Lawn to participate in a social media trend that takes place every spring across the country: posting photos and videos of themselves in their college sweatshirts.

The 47-second Instagram Reel, set to the song “I’ll Always Remember You” by Hannah Montana (lyrics: I always knew this day would come / We’d be standing one by one / With our future in our hands / So many dreams, so many plans), cuts rapidly between seniors displaying college sweatshirts representing Stanford, Brown, Northwestern, and other highly ranked colleges. The video garnered over 300,000 views within three weeks.

Social media posts like these are celebratory, commemorating a significant milestone in the life of a high school teenager. While they serve as a meaningful and joyful marker of achievement, their public nature also makes them easily accessible—and open to scrutinty—from peers, parents, and the wider community. Content like this can feed a narrative that favors students who attend highly ranked schools over those who attend universities that might be ranked lower but align better with their interests and values.

In the same form, survey data shows that 65% of respondents across all grades expressed a belief that attending a highly selective college was important to fulfill expectations that their parents held.

Aryan M. ’25, who will attend the University of California, Berkeley next year, agreed that external pressure from parents to apply to certain schools exists, but proposed multiple reasons for the possibility.

“I know some people whose parents went to one school and really want their kids to go to that same school,” Aryan said. “Or it can go the other way, since [generally] a lot of immigrant parents who may not have had the chance to go to a prestigious school want their kids to.”

He suggested that parental expectations may come from a sort of “self-fulfilling prophecy,” where they see other Bay Area parents celebrating their kids who will attend selective schools, and subsequently compel their own children to strive for that goal.

Ultimately, these influences can reinforce a persistent cycle of self and externally imposed pressure.

“I would say people’s parents have high expectations. I think students [also] have high expectations for themselves,” said Livie P. ’26. “[But] seeing all these students who graduated and have gone to amazing schools has created a sort of atmosphere of, like, ‘I’m expected to go to those schools.’”

College counselor Paul Gallagher explains that Nueva’s college counseling program is designed to be highly personalized and attentive to each student’s unique experience. He emphasizes the importance of building close relationships with students to create a supportive environment where influences—whether cultural, individual, or parental—can be recognized and addressed.

“We implement a counseling program that is very individual, so there’s nothing like a forced march through the application,” said Gallagher, who shared that the college counseling team—who also serve as coaches, advisors, and trip chaperones—get out into the community so that they can better know and understand the students they work with. “Hopefully, by doing that, we give students a relatively safe space for them to admit how they are being influenced.”

Part II: Beyond the College Sweatshirt

Each year, review websites like US News & World Report and Niche generate “best college” rankings. Families look to these rankings as a benchmark, and schools consistently landing at the top become household names associated with prestige. But there is no objective definition of a “top school.”

In spending time researching schools and working through the application process, some seniors realized that rankings weren’t an important factor in selecting the schools they applied to. Survey data indicated that 71% of seniors believed it was important for them to attend a highly selective college, and 48% believed that attending one would be representative of their academic success and value.

These numbers were higher for the other grades: 87% of freshmen, 88% of sophomores, and 88% of junior respondents believed it was important for them to attend highly selective colleges, and 70% of freshmen, 65% of sophomores, and 72% of junior respondents believed that attending one would be representative of their academic success.

Nathan S. ’25 and Leo S. ’25, who will be students at Santa Clara University and Boston University, respectively, found that the meaning of college rankings diminished when visiting and touring the campuses, citing how they realized many schools felt very comparable regardless of selectivity.

“I had a very similar experience and mindset [to the younger students]. I would always look at top-ranked schools,” Leo said when looking at the survey data. “But at the end of the day, they’re all very similar. I find it strange that [ranking websites] are able to find such clear differences between these schools, because you’re going to have a great experience wherever you go.”

Additionally, Nathan pointed out that a school’s ranking is just one statistic that factors in numerous metrics about the school. To him, the specific academic program he was interested in was significantly more important.

“It’s a number that doesn’t mean that much to me. Because I’m somebody who’s interested in STEM, applying to the number one liberal arts school in the country just wasn’t that appealing to me,” Nathan said. “I don’t think that would serve as a measure of my success or academic achievement, because it’s not what I’m looking for.”

The idea of “best” is subjective and can hold a different meaning for every individual. Lara M. ’25, who will attend the University of North Carolina next year, finds that this sentiment rings true.

“I chose UNC over schools that are ranked higher, or often perceived as ‘better,’ because of the specific program that I’m in and the opportunities that I’m going to get because of that,” Lara said.

Part III: A Nueva Definition of Success

Many selective universities with low acceptance rates clarify in their application process that they consider a holistic review of each applying student. The factors they consider include essay quality, the applicant’s traits and character, their extracurricular involvement, and academic performance.

In a survey conducted by The Nueva Current last year, following the COVID-19 pandemic, a majority of students received all As in their coursework (81% of grades awarded were flat As) at Nueva. Additionally, Nueva prides itself on its efforts to reduce competition among students. The school does not calculate GPA, track class rank, offer AP courses, or recognize a valedictorian or salutatorian. Still, a competitive mindset can emerge and the effort to stand out from one’s classmates manifests itself in other ways.

“I don’t feel like people are competing to get all As because it’s not an exclusive thing,” said Hannah F. ’27. “But it’s pretty common after a test for people to ask around, like, ‘Did you get this question right or wrong?’ because they want to [compare answers to] know where they stand in the class.”

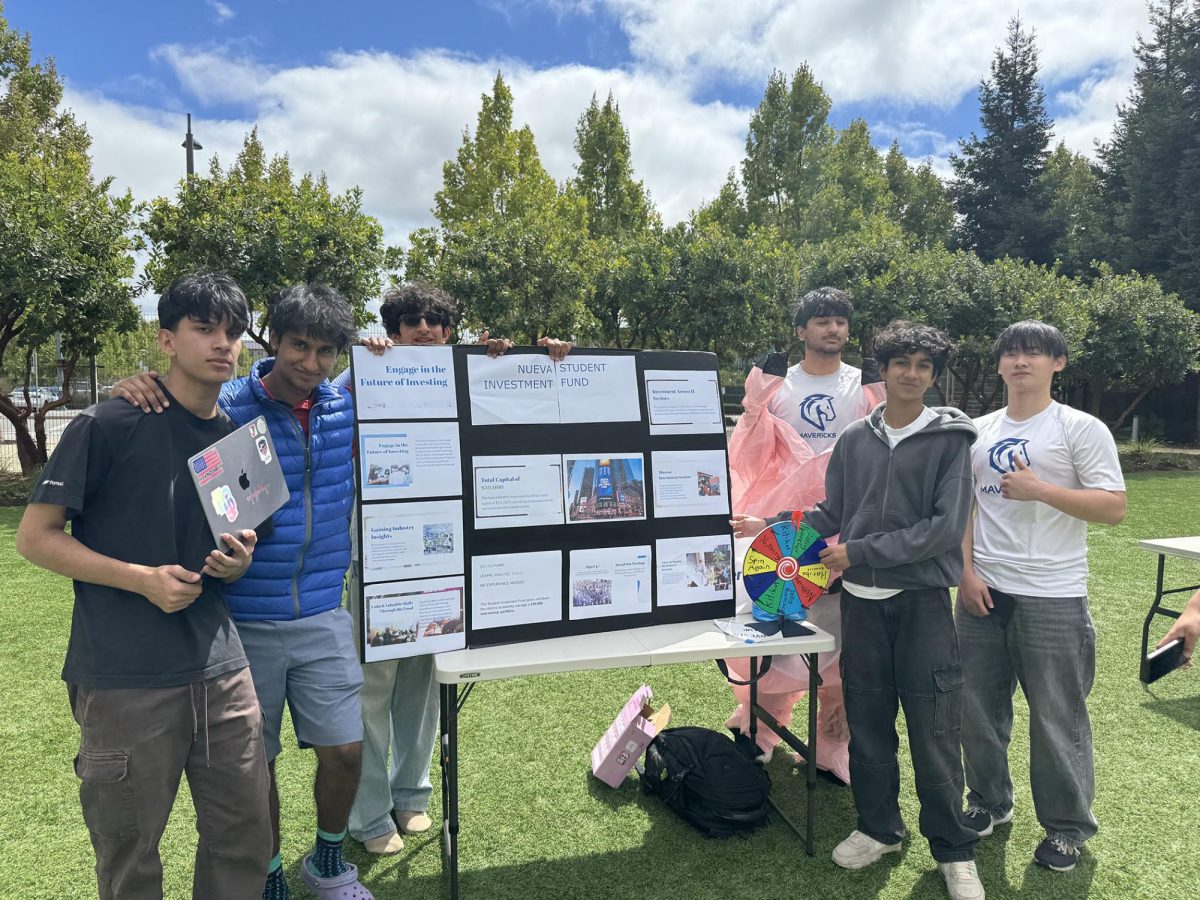

To stand out from their peers, students can turn to extracurriculars as a way to stand out from their peers. This chase for extracurriculars—sports, volunteer hours, club leadership positions, internships, and more—has some students feeling out of place and concerned about their perceived uniqueness.

“It’s hard for me to admit this, but I often feel worried when I hear about my peers’ accomplishments,” another anonymous freshman wrote on the survey. “I’m afraid that I will not stand out compared to them through a college lens.”

These feelings of uncertainty and self-doubt aren’t uncommon among students navigating the pressures of college preparation.

“I wonder whether doing extracurriculars at a pace similar to my peers to help improve my resume is something I should be doing,” an anonymous junior said in an interview. “Am I not focused enough on college? Am I too focused on college? I don’t even know.”

Some students feel pressured to try and participate in certain extracurricular activities, even if they may not be as interesting to them as other activities.

Early in his junior year, Carson M. ’26 joined Food4All, a food insecurity nonprofit organization founded by students at Los Altos High School, but he quickly left soon after when he recognized he no longer enjoyed working in the organization.

“I thought it would be a strong addition to the resume and would demonstrate initiative and leadership in a community service setting, which I was missing at the time,” Carson said. “After a few months, I realized it was just a club that dozens of other kids were doing with the same intent I had coming into it, and I needed to start something unique, original that I could claim for myself.”

Carson’s observation of local high schoolers pursuing activities for the sole purpose of checking boxes on their resume is not uncommon, reflecting a broader culture of performative involvement driven by college admissions pressure.

According to the survey, 38.94% of the surveyed students self-reported prioritizing extracurriculars they aren’t as interested in, but are perceived to look more attractive to admission officers over hobbies or personal interests. When asked to think about other students at Nueva, 92% of respondents agreed with the statement, “I believe that my peers join or have joined activities that they are NOT very interested in because they believe that it will make their college application or resume look better.”

“I think this is a big problem, especially with students in leadership,” an anonymous freshman wrote. “It takes away from the idea of servant leadership and makes the role more self-centered.”

For Carson, the pressure of ensuring that the college resume only contains “desirable” or most impressive extracurriculars leads students to abandon activities or hobbies they once enjoyed. These activities are frequently dropped not because of a lack of interest, but because they’re seen as offering little value to a college application compared to other, more strategic options.

Carson used to be a pianist and loved to play the piano, but he decided that even though he enjoyed playing, it was not worthwhile to continue. He put piano on hold and replaced it with more activities with a higher perceived value.

“I realized at a certain point that I need to be more practical. This is just sucking up time that I don’t really have,” Carson said. “I recognized the decision was correct, so I wouldn’t say it was something I regretted, but there was a part of me that was a little annoyed. In an ideal world, there are so many other activities that I would be doing and activities that I’m doing now that I would not be doing because they’re servicing my passions.”

Part IV: Running Their Race

From self-questioning and the pressure to participate in as many extracurriculars as possible, an uncomfortable environment surrounding the college application process emerges, but remains hidden beneath the surface—often becoming visible when acceptance decisions are announced and peer comparisons intensify.

Connor H. ’26 has noticed tension, jealousy, and judgment among peers during college acceptance season, especially when news spread about which seniors were admitted to which schools. He observed that once someone is accepted into a highly selective university, others begin to scrutinize that person’s college resume, trying to understand what set them apart that they were admitted.

“I remember a person got into a great college through Early Decision, and then I overheard conversations with different people about how they got in,” Connor said. “As soon as people found out, they were talking about it and trying to justify it. Do they have legacy there? What did they do? They were so certain that this person didn’t have their own merits.”

In some cases, curiosity around college admissions goes beyond casual conversations and turns into direct, and sometimes uncomfortable, questioning. Lara has experienced this firsthand, with peers approaching her multiple times to express surprise or other judgment about her decision to attend UNC.

“I often wondered, why are they judging me that way?” Lara said. “But some people have said, ‘Oh, they’re judging you because they see a lot from you, so they expected you to go to a ‘better school.’’ Or, ‘they’re just judging you because they don’t understand the value of the school and the program that you’re going to.’”

Rather than letting the judgment affect her, Lara remains confident in her decision, pointing to its strong community, helpful resources, and emphasis on learning—qualities she values more than name or brand recognition of other schools.

Besides peers and family members asking well-meaning but direct questions, the pressure to succeed academically has led some students to distance themselves from friends and devote more time to studying. Livie, for example, has felt the pressure and has begun to prioritize school during her free time to maximize productivity. While she made the decision to focus on academics with college admission as her goal, she still often feels overwhelmed by her decision.

“Feeling like other people could balance extracurriculars in school and a bunch of other things, and I couldn’t, made me feel definitely like an outlier,” Livie said. “I was different, or made it make me feel jealous of other people in a way, because they’re able to do this and that and still appear fine, and I can only do one thing at once. That makes me feel like it’s gonna be difficult for me to get into the colleges I want compared to other people who are doing all these things.”

It’s natural for some students to feel external pressure from peers, leading to resume stacking, self-doubt, and judgment. Despite these challenges, the school takes some exceptional and uncommon steps to minimize academic competition between students: the elimination of AP courses, avoiding student rankings, fostering a curiosity- and passion-driven environment, and having college counselors who emphasize finding a college that fits each student’s personality, interests, and learning styles. At the start of the fall semester, seniors also gather to come up with a collective agreement on norms around the college admissions process, which can include ways to talk—or not talk—about the process. Students appreciate these approaches, which can complement their own individual efforts to mitigate pressure.

Aadit B. ’26 tends to focus on his own work and goals rather than comparing himself to his peers. By practicing “gratitude,” he feels confident about his accomplishments; instead of comparing himself to the people around him, he minimizes feeling the competitive atmosphere intertwined with college applications.

“At the end of the day, the people around me will always be there for me,” Aadit said. “I want to be there for them during a time where there might be a lot of stress, whether they want to admit it or not.”

In an email to the freshmen class last week with the subject line “Transitions,” 9th grade dean Patrick Berger noted the inevitable stress that can come with the onset of grades and the looming college process. He acknowledged the tension with Nueva values that the addition of grades in 10th grade creates. In his final email to the freshmen, he wrote, “Despite the pressure that can come from grades—and the college admissions process that necessitates their existence, I hope you will preserve ideals such as the importance of each student following their passions, determining their own goals, and being compelled to learn through internal motivation and the intrinsic value of knowledge.”

“Over the next several years, I hope that you will be able to still preserve these ideals despite the pressure that can come from grades and the college admissions process that necessitates their existence,” he continued. “Don’t miss your opportunity this final week of the semester to have frank and constructive dialogue with your teachers without the specter of grades looming in the background. Your world becoming more structured over the coming years does not mean the same has to happen to you.”

Additional Research by Athena C. & Aryan M.