Mike Swire, an environmental activist who lives in Bay Meadows, is known for being the “bike lanes person” at San Mateo city council meetings.

“Every night I go to a meeting or two, and they’re like ‘Oh, here’s Mike again,’ and they’re a bit sick of me,” Swire said.

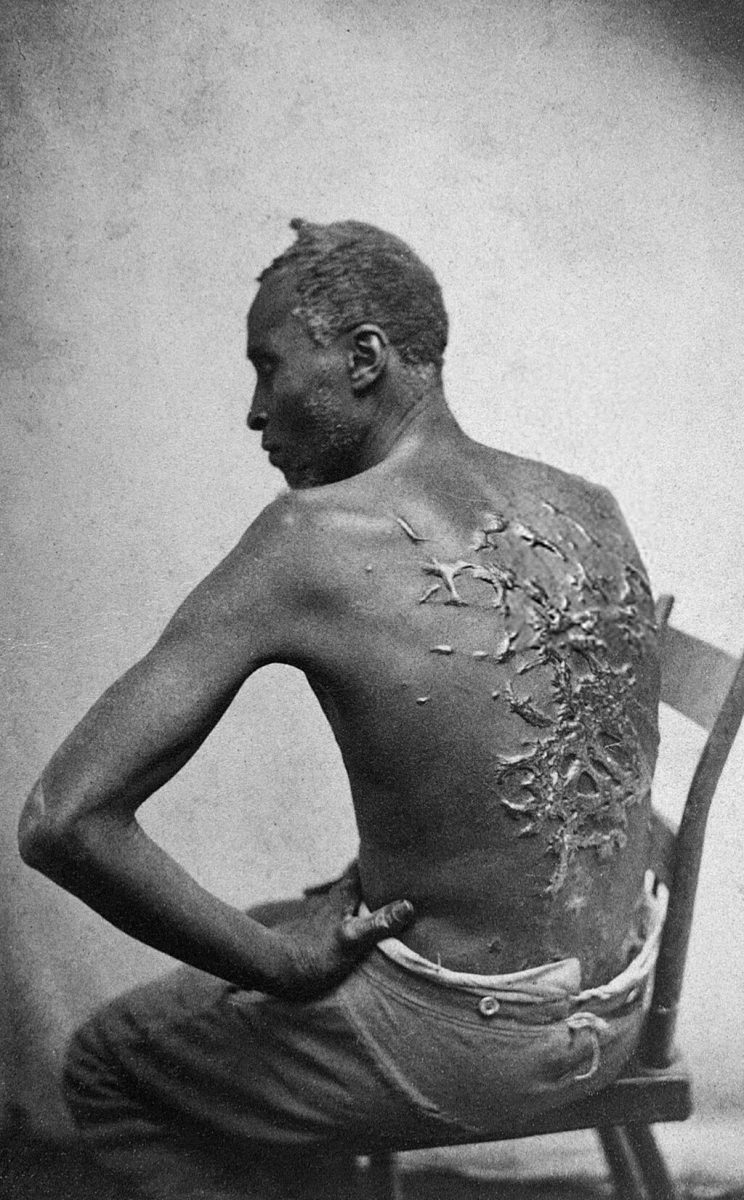

The grumbles don’t deter Swire from his mission. He views the development of safe and protected bike lanes as one of the biggest equity issues facing San Mateo.

“There’s this misperception that the people who use bike lanes are middle-aged guys, and that’s not true,” Swire said. “If you go down to Humboldt, North Central, it is an equity priority neighborhood, and a lot of people there don’t have cars. So, bike lanes are the way they get to their job.”

Swire has been working in politics since he was in college, but has spent the past three years exclusively focusing on safe streets on the peninsula, which includes biking and walking as well as sustainable transportation. He said one of the biggest obstacles to safe streets in San Mateo is tax revenue being directed toward highway projects.

“Highways are the biggest sources of greenhouse gas emissions, air pollution, and crashes,” Swire asserted. “They say widening highways reduces congestion, but all it does is encourage more people to drive and, eventually, congestion returns.”

Swire, echoing the views of many environmental advocates, argues that even if expanding bike lanes means sacrificing some parking spots or extra traffic lanes, the long-term benefits—less congestion and fewer cars on the road—make the sacrifice worthwhile. He said safety is still one of the biggest concerns San Mateo residents have to face when deciding to bike or drive.

According to a recent survey of 50 Upper School students, over 50% of students who bike have felt concerned about being hit by a car. Additionally, 65% said that if there were more separated bikeways (dedicated lanes separated with bollards/parking), they would bike more often, while only 19% said they would bike more if there were more bike routes without dedicated lanes.

One of those student bikers, Elin Randolph ’28, rides her bike daily to the Caltrain station to get to school; her commute to the station is 2.5 miles and takes around 15 to 20 minutes, depending on traffic. Recently, her biggest worry has been the removal of bike lanes on her usual route due to construction.

“I feel a lot less safe, and I think my commute is a lot more dangerous, especially because there are cars that don’t know how to deal with bikes sharing the street with them, even though that’s how it’s supposed to be using traffic laws,” Randolph said.

Upper School Social Emotional Learning Teacher Sean Schochet also bikes to school and has been passionate about biking since he was in high school. He feels that the “shared roads” that San Mateo puts in place to encourage biking are performative and unsafe.

“Sometimes I’m getting honked at and I’m legally in my right of way using the lane because there’s this bicycle painted on the road, but cars don’t respect it and it’s dangerous,” Schochet said.

Schochet views biking safety as an issue that needs a shift in mindset from the community, along with safe infrastructure and support from the government.

“The community doesn’t just transform into a biking community overnight by putting in lanes,” Schochet said. “It’s actually over time that bikers are seen on the roads, and that mindsets shift. People should be watching out for bikers and anticipating them more, because anticipation makes it safe as well.”

One example of how anti-bike lane mindsets can influence policy is the bike lanes on Humboldt Street. In 2022, protected bike lanes were installed along Humboldt and Poplar Avenues as part of a $1.5 million federal grant. However, the initiative also removed about 200 parking spaces from the area, angering some residents. On Monday, Feb. 3, council members decided to start the process of removing the bike lanes on Humboldt Street from Second Avenue to Indian Avenue to appease these residents.

“This is a perfect case of quick judgment and not letting a solution become the solution,” Schochet said. “They are overreacting to community outrage, in my opinion, without any data to see if it’s working or not. Two years is way too short a time, because even if fewer riders are using it, over time, more riders would use it if they saw other riders using it, and then it would build up into a community that might utilize it more.”

Additional Research by Cat F. ’25